When you visit Sovereign Hill, you see lots of different kinds of costumes being worn by the staff and volunteers in the streets, shops and on the diggings. All our costumes tell stories about the kind of people who were really here in Ballarat in the 1850s. Some of our most photographed costumed characters are the Redcoat Soldiers, who tell the story of the British Army’s role in 19th century Victoria.

Students often ask, ‘Why are they wearing bright red jackets? Soldiers today wear camouflage to hide in the bush, but a red jacket can’t hide you anywhere!’. These jackets, which are actually called coatees, were red for a number of reasons:

- Red dye was cheap and had already been the colour of most British Army uniforms for hundreds of years by the 19th century.

- Dressing your team in one bright colour stopped you from shooting them by accident with your smoky gun on a smoky battlefield (smokeless gunpowder was only made available to the British Army in 1880). Until the 20th century, armies fought at close range, and usually in lines in a field, so they had no use for camouflage until the fighting style changed when modern longer-range weapons were invented.

- In the 1850s, the British Army was the most powerful army in the world – they had the best weapons and the best training – so they wanted their enemies to recognise them from a distance, and then run away to avoid being killed!

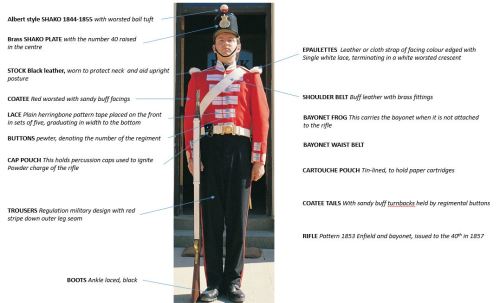

The Redcoat Soldiers played an important role in the Eureka Rebellion and their daily parade around Sovereign Hill is one of our most popular events. We need to keep them looking ‘spiffy‘, so our Costume Department recently began a big project to make new uniforms for our hard-working soldiers.

Every time our Costume Department makes a new outfit for one of our staff or volunteers, the team starts by doing some research. There are lots of paintings, photographs and written descriptions of the Redcoat Soldier uniforms, which help us re-create their outfits to look just like the real ones worn in the 1850s. We were very lucky in this instance to find a real 1840s-50s Redcoat coatee in the collection of a local history buff, which revealed secret pockets inside the coatee ‘tails’! We think these would have been used for storing gloves and hiding important documents. Next time you visit Sovereign Hill, ask a Redcoat soldier what he hides in his secret tail pockets.

This very old, fragile coatee also helped us understand what the lining and internal structure of the coatees should be, which not only makes them more comfortable for the people wearing them, but also makes those people look more muscular and broad-shouldered.

The coatee was designed to make the chest of the man wearing it (only men could be in the British Army in the 19th century) look like a triangle (women desired to be hour-glass shaped), and epaulettes would be attached to the shoulders to make them appear even bigger. If you were an important officer in the regiment (team of soldiers), you would have received a ‘uniform allowance’ as part of your wages which you could use to decorate your coatee further.

Left: An 1850s shako. Right: Sovereign Hill’s re-created shako.

The Sovereign Hill Costume Department have now created three different kinds of Redcoat uniforms for our daily parades: an officer’s uniform (in scarlet red), and soldiers’ uniforms and a drummer’s uniform (in madder red). We were able to achieve the correct coatee colouring thanks to information from a uniforms supplier in England which has been making outfits for the British Army since the Battle of Waterloo – more than 200 years ago! Many details like buttons, pom-poms and embroidered trimmings for the new costumes had to be made by hand by skilled craftspeople, which took a lot of hard work to organise. Re-creating the hats – or shakos – presented one of the biggest challenges to the Costume team, but the new Redcoat costumes are nearly finished and ready for the daily parade.

All of our costumes tell stories about the history of clothing dyes, innovations in sewing techniques and machines, and developments in the manufacture of textiles, as well as showcasing the fashions of the time. The popular fashions of the 1850s also tell stories about community values and ideas about masculinity and femininity. What do your clothes say about you and the community you live in?

Links and References

Read about the role of the Redcoat Soldiers in the Eureka Rebellion: https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2011/08/15/the-redcoats-connecting-history-lessons/

Sovereign Hill’s Redcoats firing their guns: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=loLdcXa0_w8

A wonderful V&A webpage about 19th century fashion: http://www.vam.ac.uk/page/0-9/19th-century-fashion/

Learn about ladies’ weird 1850s underpants…: https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2013/09/06/gold-rush-undies-womens-fashionable-underwear-in-the-1850s/

What did children wear during the gold rush? https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2012/11/26/gold-rush-babes-childrens-fashion-in-the-1850s/

Men’s 1850s fashion: https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2012/07/17/gold-rush-beaus-mens-fashion-in-the-1850s/

Women’s 1850s fashion: https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2012/02/28/gold-rush-belles-womens-fashion-in-the-1850s/

The British Army during Queen Victoria’s reign: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Army_during_the_Victorian_Era

A social story for ASD students preparing for a Sovereign Hill visit: http://www.sovereignhill.com.au/media/uploads/Here_come_the_Redcoats.pdf

![014EVA000000000U04195V00[SVC1]](https://sovereignhilleducation.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/014eva000000000u04195v00svc1.jpg?w=500)