When you visit Sovereign Hill living museum, you can immerse yourself in what life was like in Ballarat during the goldrush. As you wander through the museum, you travel in time through the different phases of the goldrush, from the chaos of the diggings (1851-54), to the industrialisation of gold mining in the steam precinct (1860s – 1890s).

The diggings area is a small microcosm of what the goldfields would have looked like at the start of the goldrush in 1851. Before the goldrush, Ballarat was a sheep farm, and prior to 1838, this was undisturbed Wadawurrung Country.

When tens of thousands of people from all around world flooded into the area from 1851, there were no buildings or infrastructure in place to support them. The population was mostly itinerant – just passing through – here to try to find gold, and then they’d leave. The gold seekers built a temporary ‘tent city’ to survive. As these early structures were not intended to last, they did not survive for very long.

So how did Sovereign Hill know what the goldfields looked like during this period if none of it survives today? In the early 1850s, photography was in its infancy and quite cumbersome; materials were expensive, the process time-sensitive, and the chemicals required needed to be imported from overseas. With so few surviving photographs capturing this period, artists recording what they were witnessing on the goldfields are invaluable to our understanding of what the goldfields might have looked like.

One of the most celebrated goldfields artists is Samuel Thomas Gill. Gill was born in Somerset, England, in 1818. He trained as an artist in London before migrating to Australia with his family in 1839. He set up a studio in Adelaide painting portraits of people as well as “horses, dogs… with local scenery.”

Albumen print of S.T. Gill in Albums of photographs of actors, actresses, singers, music hall artists and others, 1854-ca. 1910, vol. 6. State Library of New South Wales collection, FL517206.

Gill struggled to make a decent living as an artist and declared bankruptcy in the 1840s. When the Victorian goldrush kicked off, along with thousands of others across Australia he packed up his life and ventured to the goldfields to try to change his fortune. While he didn’t find gold, the melting pot of cultures, eccentric characters and oscillating fortunes on the goldfields offered Gill rich stimuli for his art.

In his sketches and paintings from the period, he recorded the rapidly transforming landscape he was witnessing. They allow us to experience this very specific time and place from Gill’s perspective. We have utilised Gill’s paintings to recreate structures, scenes and characters from the goldfields here at Sovereign Hill.

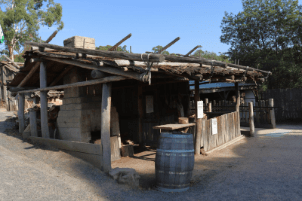

Butcher’s Shambles

Left: Butcher’s shambles near Adelaide Gully, Forrest Creek, ST Gill, 1852. State Library of Victoria collection, H7828. Right: The recreated Butcher’s Shambles in the Sovereign Hill diggings.

From 1835, Aboriginal people across Victoria were violently removed from their lands by settlers to establish farmland. Many settlers were breeding sheep to harvest their wool, our most lucrative export before the goldrush. By the start of 1851, there were around 77,000 people in Victoria, and six million sheep. In February, disastrous bushfires known as the Black Thursday fires resulted in the death of over one million sheep, reducing the sheep population to five million by the start of the goldrush.

Sheep were also utilised for their meat, with many settlers surviving on stew made of mutton – sheep over 12 months old, a gamier, fattier meat – with damper. The lack of fresh fruit and vegetables led some on the goldfields to suffer from scurvy, a vitamin c deficiency which could lead to bleeding gums and lost teeth.

Gill continued to paint his specialty of horses and dogs, including them in many of his goldrush images – such as the small dog in the image here.

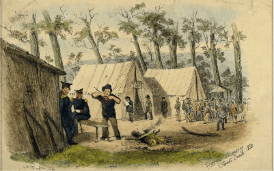

Sly Grog Shanty

Left: Sly Grog Shanty, S.T. Gill, 1852-3. Sovereign Hill Museums Association collection (96.0115.24). Right: Sovereign Hill’s recreated Sly Grog Shanty.

When word broke about the discovery of gold, all but two of 40 policemen in the colony resigned to join the goldrush. Tens of thousands of people from all around the world were swarming the goldfields. The stakes were high, leading to tensions and crime as unlucky diggers resorted to desperate means. One of the strategies the colonial government introduced to try to bring order to chaos was banning the sale of alcohol on the diggings. This certainly didn’t mean there was no grog, and here we have recreated a ‘sly grog’ tent depicted by Gill which not so subtly advertises ‘other drinks’ along with soups, meals and coffee.

The Government Camp

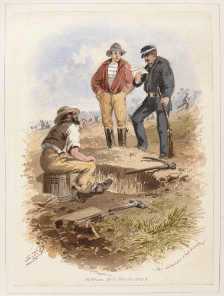

Left: Diggers Licencing, St Gill, 1852. Sovereign Hill Museums Collection, 96.0115. Right: Government camp at Sovereign Hill.

Gill captured many scenes of the attempted governance of the goldfields, including the use of Native Police and military ‘Pensioners’ brought over from Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) to fill the police void created at the start of the goldrush. In Diggers Licencing, Gill depicts diggers lining up at the government camp to purchase their gold license (sic). From 1851 to 1855, diggers were required to purchase a gold license to have the right to find gold. The price of the licence fluctuated over this time, sometimes raised to increase government revenue, and ultimately reduced due to mostly peaceful agitation by diggers over this period, such as protests, petitions and civil disobedience.

The License Inspected, ST Gill, 1852-3. State Library of Victoria collection.

By the end of 1854, the licence was £1 per month. This may not sound like much today, but £1 in the 1850s has the equivalent buying power of around $1,000 in today’s money. You had to pay for the licence even if you didn’t find gold, leaving unlucky diggers worse off after a month of back-breaking work. If you were caught on the diggings without a licence, you would receive a £5 fine for your first offence, £10 for your second, even £15 for a third. Troopers were able to keep half of the first fine, so were incentivised to charge diggers with licence evasion to line their own pockets. This resulted in unfair tactics and harassment of diggers, fuelling tensions that ultimately led to the Eureka uprising.

Gill’s captivating depictions of the goldfields established him as a successful and well-known artist. Sadly, his success exacerbated his indulgence in alcohol. The quality of his work slipped leading to less commissions. In 1880, he collapsed on the steps of the Melbourne General Post Office, apparently from an ‘aneurysm of the aorta’. Destitute and with no wife or children, he was buried in Melbourne cemetery in a pauper’s grave. In 1913, the Historical Society of Victoria raised subscriptions to erect a large tombstone, which marked in stone Gill’s legacy as ‘the artist of the goldfields.’

Written by Sovereign Hill Education Officer Ellen Becker

Discover more from Sovereign Hill Education Blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.