If we were to travel back in time likely one of the first things we would notice would be the smell. A wide array of smells we are no longer used to on our modern streets would ‘assault the nasal passages’. Newspapers and council meetings frequently included discussion of dirty streets. There is no indoor plumbing in our houses or sewer drains or pipes on our early city streets.

Discussing the draining in Ballarat East: “Mr Cathie – Do you think the want of drainage will lead to malaria, miasma, and fever?

Mr Isaacs – That is a very large array of hard words, but it means this – Will garbage cause a stink, and is a stink hurtful? I say it will and it is. (Cheers, and laughter)”

“Municipal meeting Ballarat East,” Friday 9 October 1857, The Star

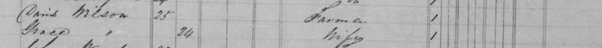

Life expectancy in the nineteenth century was much lower than today, in large part because childhood mortality was so much higher than today. Surviving to the age of 5 was a huge challenge, and mortality rates for young children could be as high as 40%.

So, what challenges did you have to navigate in our putrid past? Let’s explore one day in your life as a child on the diggings.

Accidents

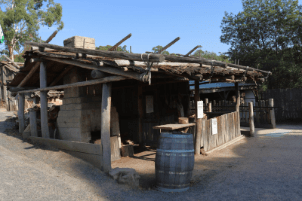

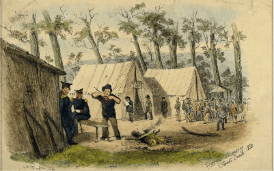

The newspaper is full of stories of childhood accidents, including at home, particularly burns. When you wake up, candles or oil lanterns are in every room and matches within easy reach (so you can find your way in the dark). Leaving the bedroom, you will find a fire burning in the kitchen or main living space and, as it is used for cooking, there may not be a screen between you and the fire. It is not uncommon for children to play near the fire. In our small goldfields homes the main room serves as the space for all the daily activities – particularly in the winter months.

Here are the common family areas in our cottage and huts. What hazards can you see?

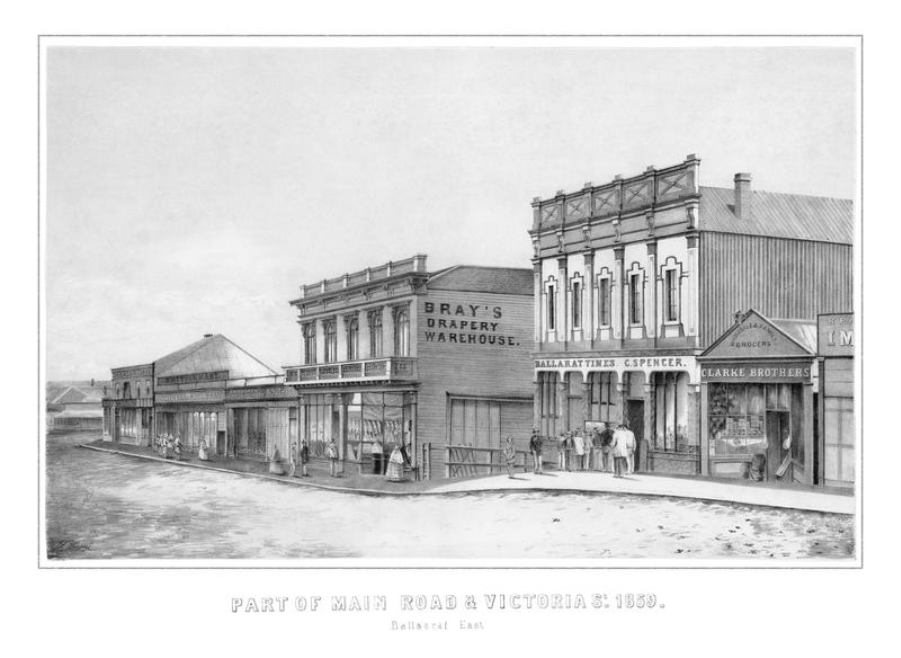

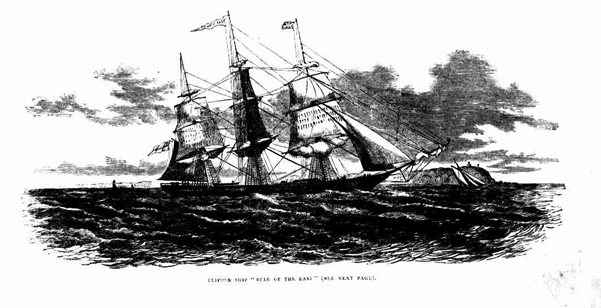

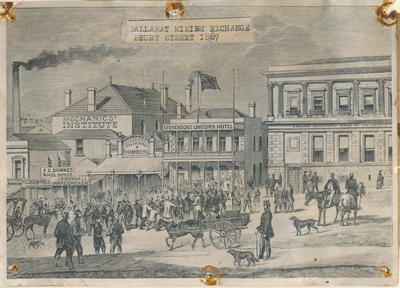

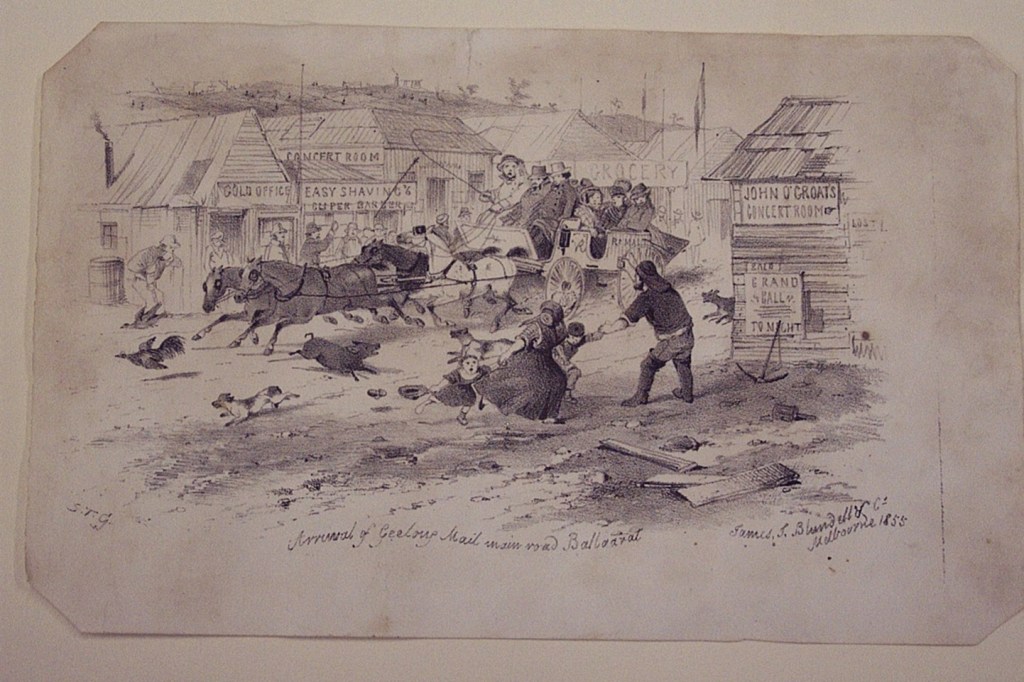

Having navigated a morning by the fire, you head into town. The opening sketch by artist Samuel Thomas Gill’s of the arriving carriage in town highlights some of the dangers in town. Roads were busy, muddy, and dirty. There was no dodging the sludge in the road, you could find yourself wading in it some days! Being run over by a carriage was a very real risk.

Children were present everywhere. Down on the diggings you might be helping your family on your claim so mind you do not slip into the water or fall down a mineshaft. Children were not always supervised by adults, and it was not uncommon for older children to supervise their younger siblings.

Don’t Drink the Water!

While slipping into creeks and dams was a risk, probably the most dangerous choice you could make on the diggings was to drink from the creek. For example, in March 1858, zymotic diseases (what we might consider infectious diseases today) resulted in 64 deaths (50 were dysentery) and 36 of these babies under 1. Dysentery is a severe form of gastroenteritis – usually caused by drinking contaminated water. No indoor plumbing or sewer system means waste sits in a pot under your bed and is then emptied into an open cess pit in your backyard. Waste from people, animals and industry eventually found its way into the main waterways.

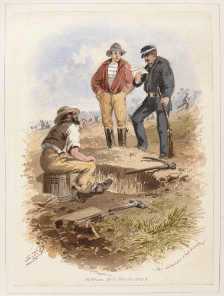

A future career choice for young boys, could be the job of nightman. His job was to empty the cesspits into his cart and take the waste out of town. He is known as the nightman because he works at night. His job is a ‘noxious’ or smelly trade that people did not want to see or smell being done.

Beware the Doctor

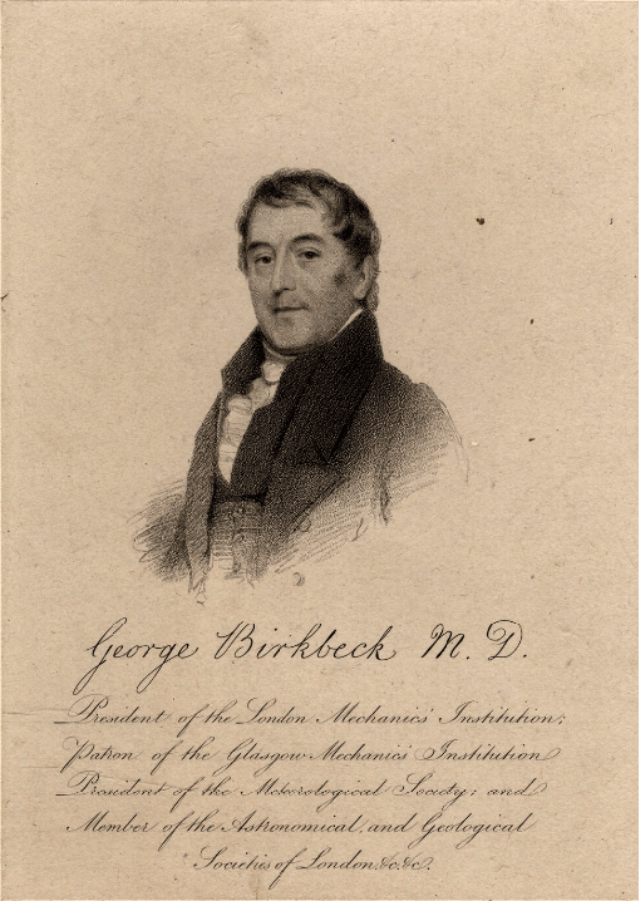

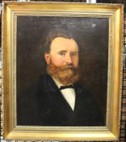

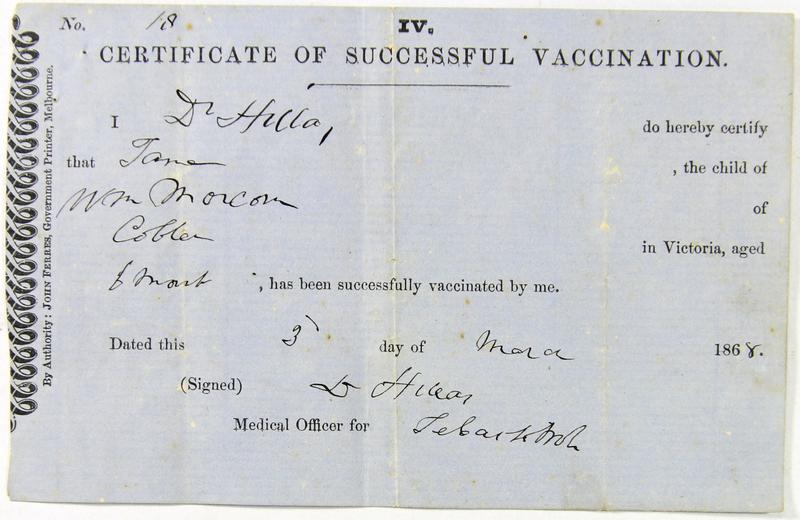

This is likely to be your Doctor, an educated gentleman, no scrubs or stethoscopes in sight. You may meet the doctor several times in your young life, not just for accidents and injuries. His first visit will be to vaccinate you against the dreaded smallpox. This will likely happen in your first six months. The doctor will make incisions in your arm, rub live lymph into your arm (probably harvested from the arm of another child), and watch over the week for your body to react. He hopes a mild illness will protect you from the much deadlier smallpox.

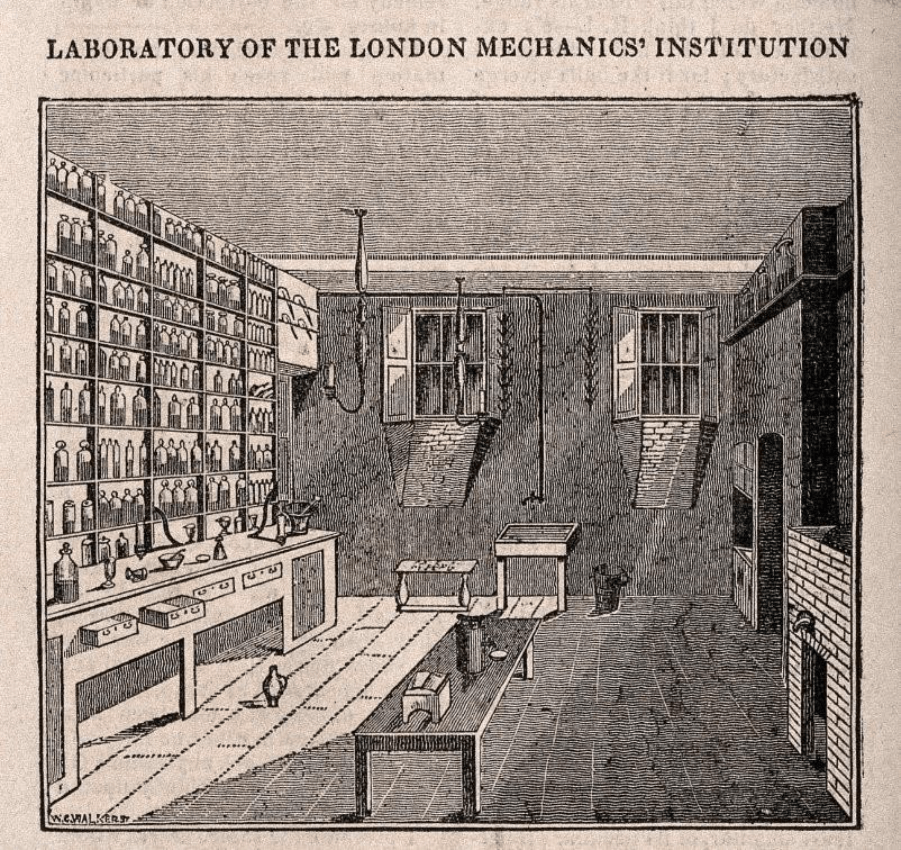

If you find yourself unwell your doctor has a variety of tools and remedies at his disposal. Some of our doctors, like Doctor Wakefield (whose rooms you can visit at Sovereign Hill) is also a chemist. His medications can include a wide variety of ingredients ranging from rhubarb, bark, herbs and spices to heavy metals like arsenic and mercury. He will likely aim to “clean out” your body with treatments to empty your belly or bowels. Sometimes he might bleed you – notice the large leech jar on the apothecary counter! In serious cases surgery might be recommended and you will see knives and saws in all shapes and sizes in the surgical kit. In most cases you will recover at home under the gentle care of a family member.

So wash your hands and stay safe on the diggings!