or, “don’t” for that matter as we never “clip our words”

In welcoming you to the nineteenth-century world of Sovereign Hill one of the first things you may notice, after the clothing, is the way we speak to each other. We will greet you with “Good Morning” or “Good Day”, never “hello”. Why is this?

“Hello” is just emerging in the late nineteenth century as a form of greeting, earlier versions of ‘hullo’ or ‘holla’ were not in common use as greetings, they were informal shouts for attention. Could you go a whole day without saying “hello”? In fact, it will take a big technological shift, the telephone, to change our use of ‘hello’. Telephones change the rules of communication when you cannot see the speaker on the other end. Legend has it, Thomas Edison championed “hello” (telephone inventor Alexander Graham Bell preferred “ahoy”)[1] as a useful greeting.

[1]“Quick Facts: Did Bell really say ahoy?” https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/ahoy-alexander-graham-bell-and-first-telephone-call accessed 21 Feb 2024

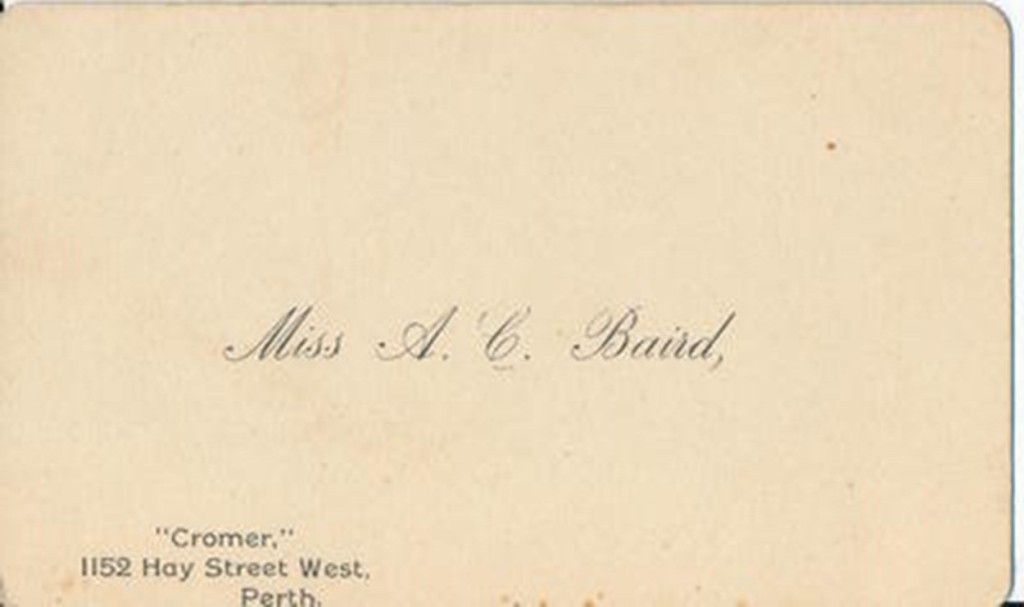

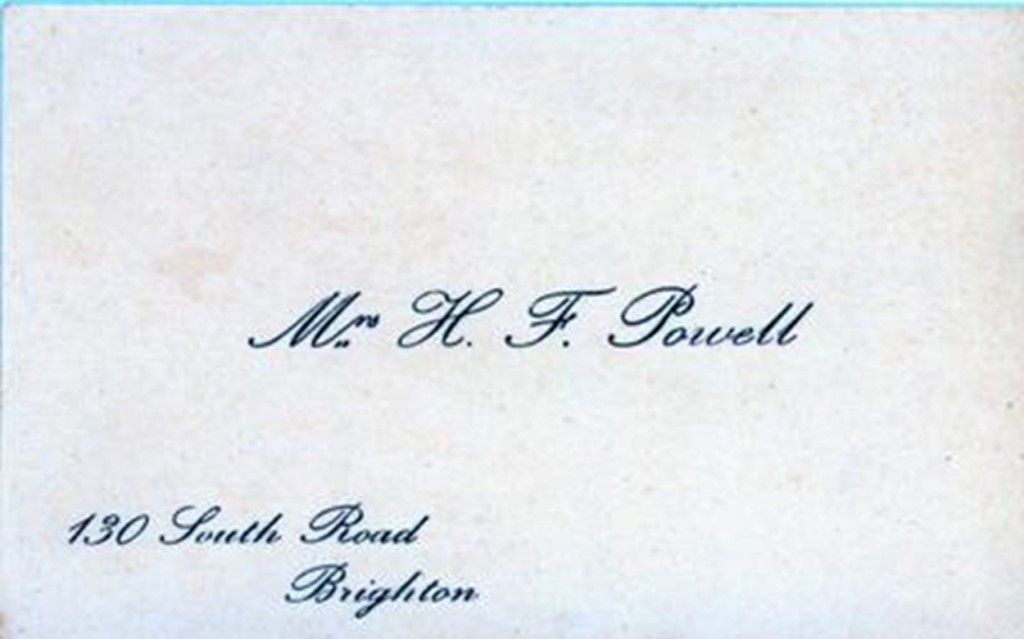

Before telephones, letters and calling cards provided introductions. You would leave a card, with your title and name, as an invitation to speak. We have several examples of these visiting cards in our collections. How many cards you left, whether you left a message on the card, or perhaps bent a corner of the card all sent a message to the recipient. It told the recipient you were home, that you were accepting visitors or that you would like to visit for example.

Is technology today changing the rules around who and how we behave when we speak to each other? Is this a good thing?

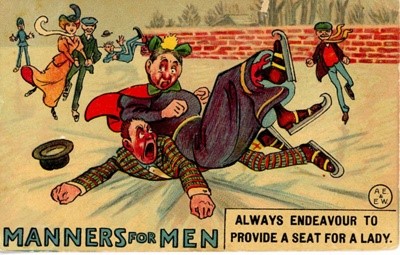

In our pre-telephone world, there are very clear rules around how we look at each other (or don’t!), move around each other and speak to each other depending on our relative age, power, and how well we know one another. These rules of behaviour in society, called “etiquette”, are taught and practiced at home and at school. They are also published again and again in books of manners and our collection contains several examples.

The nineteenth century is a period of big and increasingly fast change amongst the societies from which many of our goldfield migrants come. This big, fast change is often referred to as the Industrial Revolution. Along with the advent of steam power and factory production, and the move from country life to city life came the rise of the middle class. The middle class was a group of people who did not come with titles (important family names and connections) or inherited power like the upper class, but who also no longer work in manual trades with little money, power, or education. This new group of people earn more money than it costs to live, have an education, and often professional jobs.

The rules of behaviour are becoming a really important way of figuring out whether a person belongs in good society. In the dust and mud of the goldfields particularly it can be very difficult to tell if a person comes from the same background as you and fortunes are being made and lost very quickly. In a society used to organising people based on gender and social power, if you know and follow the rules you will have more opportunities to move up in the world. According to Australian Etiquette: Rules and usages of the best society, published in 1885, “He who does not possess them [good manners] … cannot expect to be called a gentleman; nor can a woman, without good manners, aspire to be considered a lady by ladies.”[2]

You may have noticed that our rules of behaviour are distinct for men and women. In the nineteenth century, there are very distinct understandings of what it means to be ‘male’ or ‘female’.

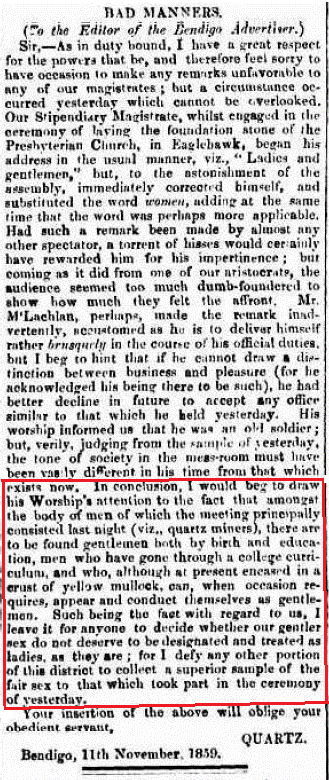

Here is a primary source example from The Bendigo Advertiser, 1859, where the writer is very upset that a Magistrate at a stone laying ceremony called the females present women and deliberately not ladies[3]. What an insult! The Magistrate’s Excuse? As an aristocrat (upper class) he should know better, but as a soldier (different social space) he may have rough manners. Appropriate titles are important and make a judgement on the person’s background.

What sort of words does the writer use that tell us how to identify a lady or gentleman?

- Gentleman: by birth, education, gone through a college curriculum, conduct

- Lady: gentler sex, fair sex

The idea that men and women are made differently, and therefore behave differently[2], shows in different expectations of men and women, including in good behaviour.

[2] Australian Etiquette, or the rules and usages of the Best Society in the Australian Colonies. People’s Publishing Company, Melbourne. 1885, p. 19.

[3] “BAD MANNERS.” Bendigo Advertiser (Vic. : 1855 – 1918) 12 November 1859: 3. accessed 21 Feb 2024 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article87993464.

[4] For an example of someone who defied social conventions, explore the story of Edward de Lacy Evans. “The Mysterious Edward/Ellen De Lacy Evans: The Picaresque in Real Life” The LaTrobe Journal, No 69 Autumn 2002 https://latrobejournal.slv.vic.gov.au/latrobejournal/issue/latrobe-69/t1-g-t9.html accessed 21 Feb 2024

Our good behaviour rules may seem unfamiliar to you, as a visitor, as how we interact with each other has become much more familiar and much more diverse in the twenty-first century. Do you have any classroom rules that you have to follow? Who made those rules? Are they different for boys and girls? Are they different for children and adults?

Meeting a new person is a good example of these changes. Our nineteenth century rules of etiquette say that we do not have to introduce someone. A formal introduction is like giving someone a good character reference for a job; if you have been introduced you must never ignore that person in future, it is very rude. Introductions must be done in the correct order: 1. Gentleman to the lady; 2. Younger to the older; 3. Inferior in social standing to the superior. Your social class decided who and how you spoke to others.

| SOCIAL CLASS | PROFESSION |

| Upper Class – landowners and investors, no manual labour | Aristocracy Rich gentry Royals Military Officers Lords Wealthy Men/Business Owners (new to this class) |

| Middle Class – skilled jobs, white collar professions with no manual labour, very class conscious | Merchant Shopkeeper Bureaucracy – railroad, bank, government |

| Working Class – skilled jobs with manual labour, unskilled jobs, poor working conditions | Trades Factory work Labourers |

| *there was also an underclass of people in extreme poverty or “sunken people” | |

When you are introducing someone, you must use their title (which can let you know marital status, job, social achievement). Titles, and pronouns, are a great example of our changing society. We greet people by first name more often, may not use titles at all and our choice of titles and pronouns is expanding to become much more inclusive of different identities.

If you visit us, you may be greeted as “Sir” or “Ma’am” as an adult, or “Master” or “Miss” as a child, titles of respect in our time. It is respectful to greet a costumed person you meet with Sir or Ma’am. “Sir” is the title given to a gentleman whose name you do not know. “Ma’am”, short for madam, is the title for a lady whose name you do not know; it comes from the Old French for my lady. You must wait for the lady to look at you and nod a greeting first, before you speak to her, and if you are wearing a hat (which of course you would be in the nineteenth century) you would touch the side of the cap as you greet her. We do not generally shake hands when we meet new people; handshakes are more common between gentlemen, and we certainly do not high five. The high five will not be invented for another hundred years in our future.

Can you imagine how the rules might change again in the future? What do you think might be different about how we greet each other and what we call each other?