Date

[ca. 1846 – ca. 1861]

http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/40191

In 1851 and 1862 Victoria produced 27,770,666 troy ounces of gold (over 800 tons), valued at about 110 million pounds at the time. The gold produced during this time was highly prized and would often be melted and transformed into different objects. Objects made from gold could include – coins, bullion, gold leaf, jewellery and even gold teeth!

Gold has been used in the making of jewellery Before Common Era (BCE) and has for many people, been seen as a symbol of wealth. Gold, being a rare metal, dominated the appearance of jewellery in the 19th Century. The gold being taken out of the earth in Ballarat from 1851 meant that by 1855 jewellery shops were appearing on the Ballarat landscape. Two men, who arrived from England, seized this business opportunity and opened a jewellery store, called Rees and Benjamin within Ballarat. You can visit Rees & Benjamin on the Main Street of Sovereign Hill to purchase jewellery.

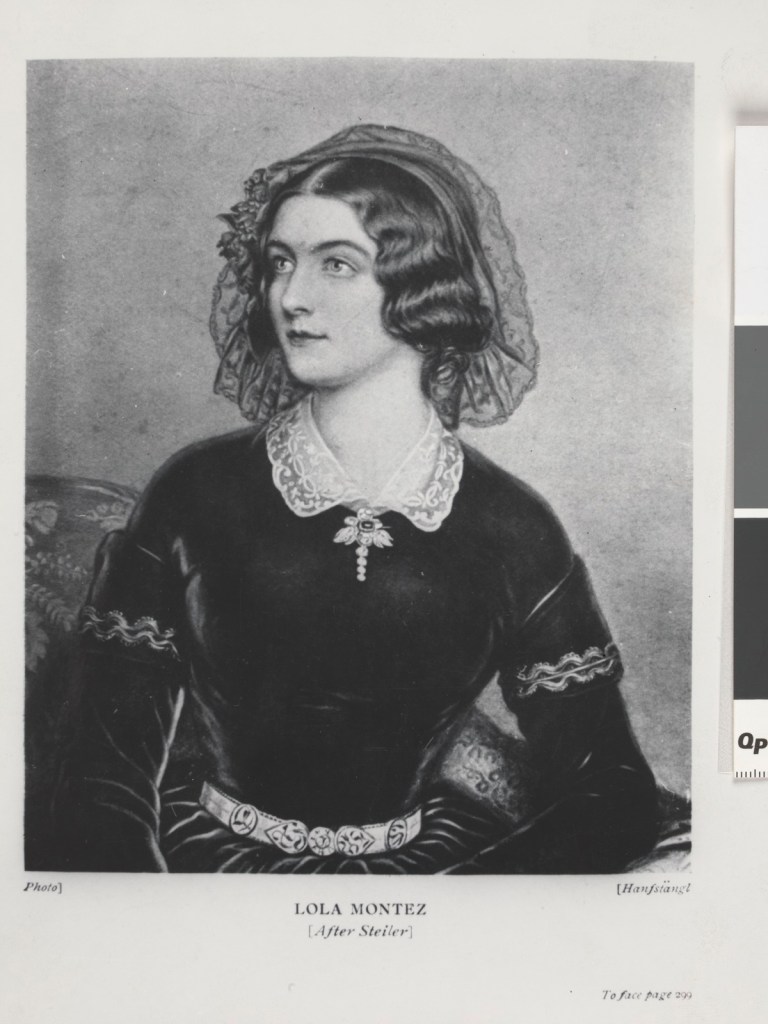

The jewellery designs in the 1850’s reflected mostly the English style. However, jewellery being made in Ballarat could also take on a uniquely Australian design of flora and fauna and even mining. One lady on the Ballarat goldfields during this time, Lola Montez, who was a stage performer, was sometimes given gold jewellery by gold miners during her on-stage performances. One gold brooch given to Lola, as a token of appreciation in Melbourne in 1855, was then later sold by her, during her travels around San Francisco (America) a year later.

Before the mid-1850s, gold was a desired resource and usually only the wealthy could afford to have jewellery pieces, made from gold and other precious materials, handmade by a jeweller. However, largely due to the gold rush and the Industrial Revolution (creating a new emerging middle class of wealth), jewellery was becoming more affordable and popular. The Industrial Revolution made the manufacturing of jewellery more cost-effective and attainable for other levels of society. The invention of electroplating (metal coating) during this time was ideal for making inexpensive jewellery, that more people could afford to buy.

One of the great influencers of jewellery fashion in the 19th Century was Queen Victoria. Her reign as Queen on the British throne went from 1837-1901. During that time, she had great influence over the world’s fashion, including jewellery. Much like social media influencers today, Queen Victoria made a societal impact on the jewellery and fashion trends during the time she reigned. Examples of popular styles of jewellery in the mid-19th Century included lockets, rings, large bangles, brooches, crosses, and necklaces. Jewellery such as earrings were also fashionable in the Victorian era. Queen Victoria had her ears pierced when she was fourteen years old and one of her painted portraits shows her wearing dangling earrings. Wearing lots of jewellery before the mid-19th century for very young girls was frowned upon. However, ladies would wear large and chunky jewellery as well as delicate bejewelled pieces.

Jewellery fashion in the 19th century was a little bit different compared to our jewellery today. Queen Victoria had a favourite piece of jewellery that she wore – a locket that contained her husband’s (Prince Albert) hair. Queen Victoria also wore and gave her children jewellery made from hair. In fact, a lot of jewellery of that time was made from hair, teeth, and animal claws. Prince Albert even designed a brooch for Queen Victoria that included their first daughter’s, Vicky, first milk (baby) teeth!

Another trend Queen Victoria made popular was that of receiving an engagement ring before marriage. Prince Albert gave Queen Victoria an engagement ring that was in a snake (serpent) design, with its tail in its mouth, entwined. In Victorian times this design symbolised eternal love. The snake design and many others would become popular amongst jewellery designers due to Queen Victoria.

In 1861, when Prince Albert died, Queen Victoria began wearing black jewellery, called mourning jewellery. This was mostly made from Whitby Jet (fossilised coal found in Whitby, England) and started a trend that lasted until around 1890.

Did you know?

- The ‘Welcome Nugget’, a substantial gold nugget dug up in Ballarat in 1858 was eventually sold to the British Mint and melted down to make minted gold sovereigns coins. The coin, on one side, would have held an impressed image of Queen Victoria on its obverse.

- Prince Albert also designed a brooch for Florence Nightingale. (Florence was named as such due to her being born in Florence, Italy).

- Sea coral was popular and used in jewellery during the Victorian Era.

- During the Paris Exposition of 1855, a life-size portrait of Queen Victoria was made completely out of hair!