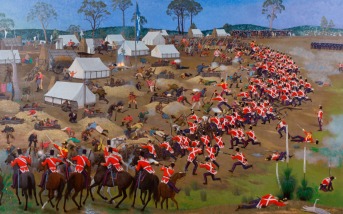

Alice Cornwall, also known as ‘Madam Midas’ ran a company mine and became a millionaire by the age of 30. Reproduced with permission from the Gold Museum.

While getting dirty hands in search of gold was viewed as a man’s job in the imported European culture of 1850s Victoria, there were many hardworking and enterprising women making a living in Ballarat during this era. In addition to managing families and households, some women on the goldfields opened shops and eateries, or worked as teachers and entertainers. There is even evidence that a few women swapped their skirts for trousers to search for gold, one became a newspaper editor, and later in the 1800s a woman named Alice Cornwall became a millionaire by the age of 30 through the company mine she owned!

Back then, it was rare for a married woman in Europe to hold a job outside her home, or to play a role in public life. However, the conditions on Australia’s goldfields provided some women with new opportunities and different lifestyles compared to their equals back in Europe. This second blogpost in our series on 1850s goldrush women explores their roles in Victorian communities beyond the home.

Working Wadawurrung Women on the Diggings

The Wadawurrung women of the Ballarat region experienced rapid changes to their lifestyles and local environment when Europeans began to colonise South Eastern Australia in the early 19th century. Therefore, by the time the gold rushes began in Ballarat 1851, historians tell us that some Wadawurrung people already spoke English and understood the new political and economic systems that Europeans had introduced. Using their skills in tanning/sewing possum skins, sourcing native food and medicine, fossicking for gold, putting on cultural performances and taking Europeans on tours of the landscape, Wadawurrung women (and men) made money from Europeans by supplying these goods and services. According to oral history handed down by members of the Wadawurrung community, European families also turned to Wadawurrung women when they needed someone to babysit their children.

Working European Women on the Diggings

In the early 1850s, there weren’t many European women living in Ballarat. As explained in Women on the Goldfields Part 1, most of the people who came to try their luck on Australia’s goldfields were European (mostly from Britain), and gold rush communities tended to be male-dominated during this time. By the mid-1850s, Ballarat had become one of the richest places in the world, and as a result of this and the government push to encourage female immigration, the number of (mostly young) women on the goldfields grew.

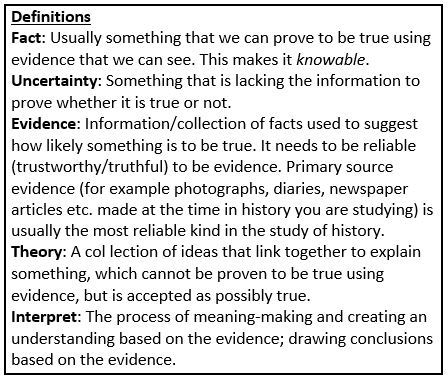

Author unknown, Bush scene, three women panning for gold, c.1855-1910. Reproduced with permission from the State Library of Victoria.

I saw the other day four or five of these fellows strolling on behind their cart. Amongst them was a young woman very well dressed, wearing a sun-bonnet … [with] a full flap behind at least a foot long, to screen the neck. On one shoulder she had a gun, and in the other hand a basket, while one of the men carried a baby, and another a swag. … You see a good many women going up on the whole, and some of them right handsome young girls. They all seem very cheerful and even merry; and the women seem to make themselves very much at home in this wild, nomadic life. – William Howitt, Land, Labour and Gold, 1855 (1972 ed.), Victoria, p.64.

Ballarat’s immigrant women proved themselves hardworking and capable, and many appear to have made the most of the opportunity to take up jobs on the goldfields. While housewifery was a highly respected family and community role for European women to perform during this era, some of these goldrush women did all of the work for their households and worked outside their homes as well.

Part of the reason some women took on extra work was due to economics. Food, clothing and household items (much of which was imported from Europe) were very expensive on the diggings, and households with two working adults usually lived more comfortably than those relying on just one income. The main motivation for these immigrants to journey to Australia in the first place was to make money, and the more creative and resourceful you were (whether you were male or female), the more successful you were likely to be.

Some women also took up work that was usually the domain of men at this time – such as school teacher, shop assistant or hotel manager – because the men in the community were too busy searching for gold to perform these roles. Since the social norms that influenced the way Europeans were supposed to behave were somewhat relaxed on the diggings, some women saw an opportunity to work and took it.

A costumed character at Sovereign Hill selling her potent ‘other drinks’ (sly grog) from her tent to support her family after the disappearance of her husband – a common goldrush experience for women on the early diggings.

Being practical and resilient were important characteristics for all to demonstrate on Victoria’s goldfields. Some women had to work because they were abandoned by their husbands. It was fairly common for men to suffer deadly accidents as a result of the dangers that come with gold mining, while others ventured to different Australian goldfields and never returned to their wives and families. When such abandoned women had children to support (and didn’t already have a job), if they could not immediately remarry or turn to charity (there was no Centrelink back then – churches did most of this type of welfare work) they sometimes had to resort to selling sly grog or even their bodies to pay the family’s bills.

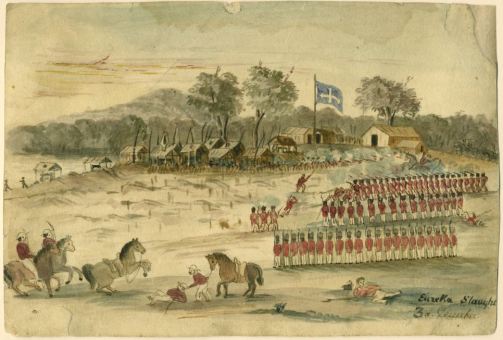

Regardless of the work they did, European women arguably built a new kind of womanhood for themselves in Australia, which challenged the gentle, modest 19th century femininity they were expected to perform. This attempt at creating a new culture was part of a broader push by the youthful and broadminded goldrush communities around Australia to challenge European social norms. Some women who thought along these lines even became involved in the Eureka Rebellion.

Anastasia Hayes was a mother, school teacher and Eureka rebel. Reproduced with permission from the Public Records Office of Victoria.

Some very adventurous European women from Victoria’s gold rushes who have interesting stories to explore include Clara Seekamp, Fanny Finch, Martha Clendinning, Anastasia Hayes, Lola Montez, Edward (ne Ellen) De Lacy, Caroline Chisholm, Anne Fraser Bon, Alice Cornwall, Eliza Perrin, Catherine Bently, Anastasia Withers, Céleste de Chabrillan, Ellen Clacy, Harriette Walters, Sarah Hanmer, Elizabeth Wilson and Bridget Hynes.

As Ballarat became a more permanent township by the 1860s, many of the women who had worked in shops etc. at the start of the gold rush began to return to full-time housewifery. Martha Clendinning was a shopkeeper during the early 1850s, but the more successful her shop became as time went by, the more her femininity and class came under question. 19th century European social norms began to be reapplied, sending women back to the private sphere – so how could she be the respectable doctor’s wife, and lady of the house, when working as a shopkeeper?

The time had gone by when, even on the goldfields, a woman unaccustomed to such work could carry on her business without invidious remarks. I began to fear my husband might be blamed for allowing me to continue at it. After the class of residents on the field had become so superior to those of the working class, whom we had found on our first arrival, to whom all species of employment for women seemed perfectly natural if they could carry it on with success. The doctor [her husband] had been most anxious and was greatly pleased when I announced my intention [of selling her shop]. – Martha Clendinning memoirs, 1853-1930.

Chinese Women on the Diggings

By the late 1850s, there were also thousands of Chinese people on Victoria’s goldfields, but only a very small percentage of them were women. The men from China mostly left their wives and children at home to care for their family farms, as most came from agricultural communities.

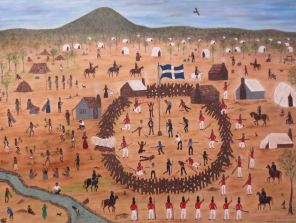

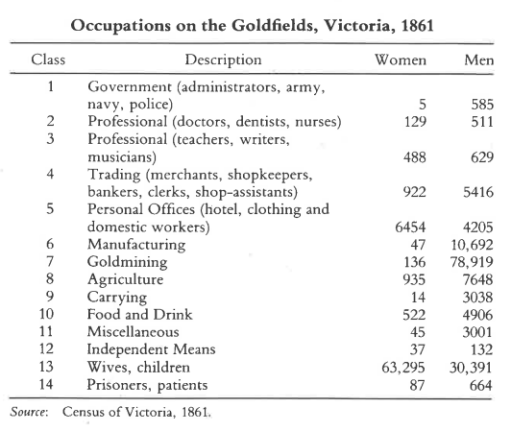

The 1861 Census of Victoria shows that women were still performing many roles normally undertaken by men at the time across goldrush communities. Reproduced from Weston Bate’s book called ‘Victorian Gold Rushes’, page 37.

Some of Victoria’s immigrant women in the 1850s were ambitious and outspoken, despite these being uncommon characteristics in women in other parts of the world during this era. However, as time went by and Ballarat became a more permanent community, the social norms of Europe directed women (regardless of whether they were European, Aboriginal, or from any other cultural background) to the private sphere (learn more about this at our next blogpost). This is where they largely stayed until Australian factories needed workers during the 20th century’s World Wars (when women replaced the men who became soldiers). Women only became permanent members of Australia’s workforce in large numbers after the Women’s Liberation Movement of the 1960-80s.

Links and References:

Sovereign Hill Education’s student research notes about women on the Ballarat goldfields: http://education.sovereignhill.com.au/media/uploads/SovHill-women-notes-ss1.pdf

A State Library of Victoria blogpost on women on the goldfields: http://ergo.slv.vic.gov.au/explore-history/golden-victoria/life-fields/women-goldfields and website about how Victorian women’s lives have changed since the 19th century: http://ergo.slv.vic.gov.au/explore-history/fight-rights/womens-rights

An SBS blogpost about women on the goldfields: https://www.sbs.com.au/gold/story.php?storyid=27#94

Dr. Claire Wright wrote a book called ‘The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka’ about the women involved in the Eureka Rebellion: https://www.textpublishing.com.au/books/the-forgotten-rebels-of-eureka

Women played many different social roles during the Victorian gold rushes: https://theconversation.com/flashers-femmes-and-other-forgotten-figures-of-the-eureka-stockade-20939

A Culture Victoria webpage about the few Chinese women living in 19th century Victoria: https://cv.vic.gov.au/stories/immigrants-and-emigrants/many-roads-chinese-on-the-goldfields/voyaging-to-australia/who-were-they/nearly-all-men/

A gender equality timeline made by the Victorian Women’s Trust: https://www.vwt.org.au/gender-equality-timeline-australia/ and a fantastic video telling a similar story: https://vimeo.com/225932476

The gender pay gap in Australian explained: https://www.wgea.gov.au/data/fact-sheets/australias-gender-pay-gap-statistics

Sex work on Ballarat’s goldfield: https://www.thecourier.com.au/story/3704053/the-brothels-of-ballarat/