Naturally, at Sovereign Hill we think everyone should learn about the Ballarat Gold Rush. Why is it such an important period in Australian history you ask? Well, in essence it changed our country in profound ways which continue to impact on the way we live today. If gold hadn’t been found in this region, Australia may have developed a very different system of government, economy and population. And without gold, Ballarat itself probably wouldn’t even be on the map! Let’s examine some of the most important legacies of the Gold Rush, including some aspects that perhaps we are not so proud of…

The impact of the Gold Rush on our government

In the lead up to the Eureka Rebellion, those involved held public meetings to discuss their ideas for making Victoria’s democracy better. Reproduced with permission from the Gold Museum.

Due in large part to the tragic loss of life at Ballarat’s Eureka Rebellion, Victoria had the most advanced democracy in the world by 1855 (Littlejohn, Marion. Eureka Stockade, Black Dog Books, Victoria 2013, p. 29). This historic event, which occurred on Sunday 3rd December, 1854, saw at least 30 people killed. It continues to be an event that historians argue about; some say it had to happen to force the government to change the taxation and democratic systems, while others say it was an utter waste of life. Historians sometimes argue that it’s a story of pesky troublemakers, or a kind of Irish uprising against the English for the long history of conflict between those two nations. Some people claim it was the start of the union movement, and the birthplace of Australian left-wing politics, while others think it was an act of terror committed by a group of extremists.

All of this debate about its significance makes it all the more interesting and important to study – and regardless of your opinion, at the time it did push the Victorian government to improve the taxation and democratic voting systems. As a result of the Eureka Rebellion, Victoria introduced the secret ballot (secret voting), salaries for members of parliament, and for the first time, most men of European descent over the age of 21 could vote. Learn more about the Eureka Rebellion here.

The impact of the Goldrush on the economy

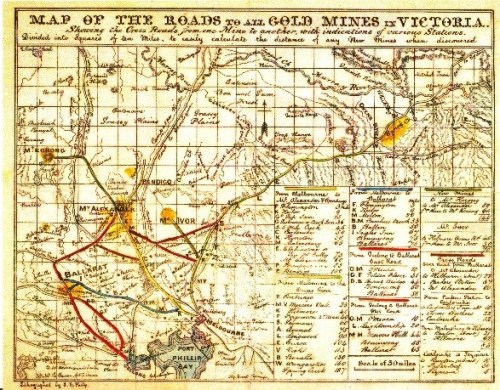

Approximately $100 billion of gold (in today’s dollar value) was discovered in Victoria during the Gold Rush (Bradby, Doug. Don’t go to the Goldfields, 2015, Waller & Chester, Victoria, p.126) making Melbourne one of the richest cities in the world! This wealth enabled Victorians to make huge investments in industrial technologies such as foundries, factories and ports, and bought us important public infrastructure such as schools, hospitals, roads, and bridges. The foundation stones for both The University of Melbourne and the State Library were laid on the same day in 1854; such huge building projects were only made possible as a result of the Gold Rush.

Most of the world’s largest gold nuggets were found in the Ballarat region, like this 68kg monster – the famous ‘Welcome Nugget”. Reproduced with permission from the Gold Museum.

Gold also transformed the structure of Victoria’s economy. Before gold, our economy was based on producing wool (sheep farming) to be exported to the factories of industrial England thus making all involved very rich. If we go back even further, the (pre-European) Aboriginal economy in this region was based on the trade of things like precious greenstone axes and possum-skin cloaks.

Many historians argue that the Ballarat Gold Rush finished when World War 1 began, as by that time Ballarat’s economy had turned to manufacturing – the city’s foundries and factories were used to make trains, shoes, woollen blankets etc. This is one of the reasons Ballarat continued to grow and thrive after the Gold Rush finished. And what is our local economy based on now? It’s based on a combination of things like healthcare, tourism and manufacturing to name just a few. Learn more about Ballarat’s 21st century economy here.

The impact of the Goldrush on Victoria’s population

Without the Gold Rush, many Victorians wouldn’t be here today. The reason many of you were born here is because your great-great-great-great grandparents immigrated to Australia in search of gold during the 19th century.

The goldfields were a true melting pot of cultures, languages and ideas. Things were harmonious at times while at others, sadly, there was racially-fueled violence in the streets. Regardless of such details, Victoria’s population exploded from about 80,000 people before gold in 1851, to more than 550,000 only ten years later (Serle, Geoffrey. The Golden Age: A history of the colony of Victoria 1851-1861, 1977, Melbourne University Press, p.382). Ask your parents and grandparents some questions about your family history – was your family in Australia at the time of the Gold Rush or did they come later as a result of it?

Some negative impacts of the Goldrush

History must not be “sugar-coated”. There are important aspects of the Gold Rush that should also be studied which don’t fill us with pride about the development of modern Australia. The first of the negative consequences of the Gold Rush involves the disruption it caused to Ballarat’s ecosystems. 160 years later there is still lots of evidence of this region being turned upside-down in pursuit of gold. Forests, animal populations and waterways are still recovering today.

Learn more about the Aboriginal side of Sovereign Hill’s Gold Rush story by exploring our new digital tour – Hidden Histories: The Wadawurrung People.

This relates to the second negative consequence of the Gold Rush – this region has been the country of the Wadawurrung People for 2,000 generations. Although there were already Europeans in Victoria (mostly farming sheep) before the Gold Rush, the huge population increase the Gold Rush brought had a devastating impact on the traditional lifestyles of the Wadawurrung People. All of the new arrivals needed food, water, and wood for houses and mineshafts, which meant that natural resources in this region were in unparalleled demand. This meant that traditional hunting grounds were turned into private farms with fences, and forests that Wadawurrung People had looked after for thousands of years to ensure they produced all of the food, shelter and fibre their population needed to live comfortably, were chopped down to be built with, or burnt in the boiler houses of the goldfields (learn more about this here). In one generation, the lives of Victorian Aboriginal People were radically transformed. As a result, the Wadawurrung People will never be able to truly practice their traditional culture, as their ancestors have done for perhaps as long as 60,000 years. These aspects of the Gold Rush story are just as important to learn about as all of the wealth and prosperity it brought to this country. Sovereign Hill recently launched a new digital tour focusing on the Gold Rush experiences of the Wadawurrung People called Hidden Histories.

So, do you think the Gold Rush is an important part of the Australian story? Does studying it help us better understand who we are now? What other periods in Australian history do you think people should learn about?

Links and references

Here’s a great Lego movie about the Eureka Rebellion made by some Victorian Grade 5 students: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wSySV9xoHzg

A brief history of Ballarat: https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ballarat,_Victoria

Information about all of the Australian gold rushes: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australian_gold_rushes

A wonderful interactive map of Australia’s gold rushes: http://www.sbs.com.au/gold/GOLD_MAP.html

Some fascinating places to visit where you can learn more about the gold rushes: http://www.visitvictoria.com/Regions/Goldfields/Things-to-do/History-and-heritage/Gold-rush-history

A video on the history of democracy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k7dTDjRnBqU&index=30&list=PL8dPuuaLjXtNjasccl-WajpONGX3zoY4M

Littlejohn, Marion. Eureka Stockade, 2013, Black Dog Books, Victoria.

Bradby, Doug. Don’t go to the Goldfields, 2015, Waller & Chester, Victoria.

Serle, Geoffrey. The Golden Age: A history of the colony of Victoria 1851-1861, 1977, Melbourne University Press.