Trains changed the world; however, nowadays their impact can easily be overlooked. For thousands of years before the invention of the train, people only had the help of horses and simple cart technologies to move themselves and their possessions around on land. When the train first arrived in Ballarat in 1862, the city celebrated in magnificent fashion; local people knew this technology would change our city forever. It confirmed Ballarat’s place on the map and was important in securing the city’s long-term success. As writer John Béchervaise has said ‘they were anticipating a marvellous twentieth century’ (Béchervaise, J. & Hawley, G. Ballarat Sketchbook, Rigby Limited, Melbourne, 1977, p52).

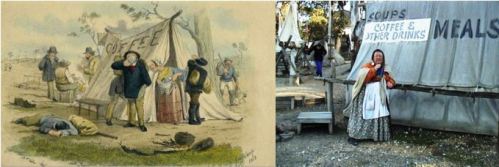

S. T. Gill’s Arrival of the Geelong Mail, Main Road Ballarat, 1855. Image courtesy of The Gold Museum, Ballarat.

Many people don’t realise that Ballarat’s CBD (central business district) hasn’t always been centred around the train station. Until 1862, the most important part of the city was along Main Road, which is where you can now find Sovereign Hill. Before the train line was built, and trains started delivering passengers and cargo from first Geelong and later Melbourne to Lydiard Street, Main Road was true to its name; it was the centre of town!

There was another reason the Ballarat CBD moved from Main Road to Lydiard Street – fire. Most of the structures built along Main Road were either wooden or canvas, and after a series of fires and the introduction of the train line, Ballaratians started building in stone around the new train station. After all, community leaders wanted to make Ballarat a more permanent, established city, and these beautiful stone buildings from the 1800s are still enjoyed by millions of tourists each year.

The City of Ballarat website has this to say about the city’s historic train station: ‘Located in the heart of Ballarat, the Ballarat Station is a gateway to the city, a CBD landmark and one of the grandest Victorian-era station buildings in the state.’

The fact that one of the first grand train stations in Victoria was built in Ballarat demonstrates the importance of this goldrush city. Ballarat’s closest port is Geelong; therefore, the first railway tracks between the two cities began construction in 1858 and the line was officially opened by Governor Barkly in 1862 to move people and cargo between the goldfields and the tall ships in Corio Bay. Interestingly, on its first journey to Ballarat, the train ran out of wood to fuel its steam engine, so the crew were forced to chop down some trees in Meredith to ensure the train made it to Ballarat. In 1889 the Melbourne-Ballarat line was opened. The station we now call ‘Ballarat’ used to be called ‘Ballarat West’ as Ballarat East had its own station which has now been demolished. The famous clock tower was added in 1891 as train travel by this time was proving extremely popular; however, as the clock itself was very expensive, it wasn’t installed until 1984!

The train’s arrival in Ballarat meant two very important things for the people of this region. It meant that individuals and businesses could receive their goods with a much cheaper delivery fee, and farmers etc. could send their produce to market much more easily. On the day the first train arrived, the train station was decorated with banners that said ‘Advance Ballarat’ and ‘Success to the Geelong-Ballarat Railway’ (Dooley, N. & King, D. The Golden Steam of Ballarat, Lowden Publishing, 1973, p4). Thousands of people gathered in Lydiard Street to welcome the train, and balls, dinners and parties were held all over the city to celebrate.

A history of Ballarat’s famous Phoenix Foundry. Find out more about this foundry and book here.

In addition to bringing the train line to the city to improve people’s lives, in 1873 Ballarat became one of the first Australian cities to manufacture trains. Ballarat’s Phoenix Foundry on Armstrong Street was the largest locomotive factory in Victoria until it ceased making engines in 1905. Businesses like the Phoenix Foundry couldn’t have existed without the railway close by.

While the train station gave Ballaratians easier access to Geelong and Melbourne, the Ballarat Train Station also provided people with access to leisure activities, like picnicking in places like Daylesford, and watching horseracing in Lal Lal. All around the station zone, city leaders have encouraged the building of what are now important Ballarat landmarks like:

- the Art Gallery of Ballarat (built in 1887, this is the oldest regional gallery in Australia with a celebrated collection of artworks);

- Her Majesty’s Theatre (known as The Academy of Music when it was opened in 1874);

- the Ballarat GPO (built in 1864, the Ballarat General Post Office is the largest in Victoria after Melbourne’s GPO in Burke St);

- The Ballarat Mechanics’ Institute (which was like an engineering/mining university, officially opened in 1860);

- and of course the Ballarat Town Hall (mostly built in 1872…).

To this day, the train station gives people access to all of these wonderful places in addition to important shopping areas and the Sturt Street sculpture gardens.

Trains gave Ballarat and its mines, factories and farms access to the big wide world. The locomotives that were manufactured here were a great source of pride for Ballaratians, as trains were a symbol of progress, technological skill, and serious financial investment for the city. Trains, like sailing ships in times past, and the cars and planes of today, changed our lives forever.

Links and References:

A fantastic video on the history of railroads around the world: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GYAk5jCTQ3s

Some great interactive photographs of Ballarat ‘then and now’: http://www.thecourier.com.au/story/1865396/ballarat-now-and-then-family-uncovers-historic-images/

The Ballarat train station on Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ballarat_railway_station

Horrible Histories on transport (song): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NLL2Txs8kCg

A short history of trains and stations in Ballarat: http://www.onmydoorstep.com.au/heritage-listing/68/ballarat-railway-complex

Bate, W. Lucky City, Melbourne University Press, 1978.

Béchervaise, J. & Hawley, G. Ballarat Sketchbook, Rigby Limited, Melbourne, 1977.

Butrims, R. & Macartney, D. Phoenix Foundry: Locomotive Builders of Ballarat, Australian Railway Historical Society, 2013.

Dooley, N. & King, D. The Golden Steam of Ballarat, Lowden Publishing, 1973.

During a visit to Sovereign Hill and the Gold Museum, it’s hard to miss the influence of goldrush artist S. T. Gill.

During a visit to Sovereign Hill and the Gold Museum, it’s hard to miss the influence of goldrush artist S. T. Gill.

![014EVA000000000U04195V00[SVC1]](https://sovereignhilledblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/014eva000000000u04195v00svc1.jpg?w=500)