During Ballarat’s gold rushes, there were many animals – both native and introduced – living on the diggings. Some were of great use to the miners and their families as a source of transport or food, while others were security guards, working animals and even served as hot water bottles. Many native animals were just living their lives but when gold mining changed their habitat, they had to relocate to different parts of Victoria as the risk of becoming extinct was high. Let’s explore the roles they played and the lives they would have led back then.

Rugs made from possum-skins like this one would keep people very warm during a cold Ballarat winter. The Wadawurrung people made these to sell to the miners, who paid a lot of money for such soft and life-saving rugs.

The Wadawurrung people encouraged certain native animals across this region for thousands of years before the arrival of the European squatters and then gold miners in the 1800s. Animals such as brushtail possums, eels and grey kangaroos were plentiful around Ballarat because traditional Wadawurrung landscape management took care of them by making sure their sources of food were in rich supply. This meant that when people wanted to make use of these animals for food or clothing, they could easily be located and collected. However, enough of each species was always left alive at the end of a hunt to ensure people living in this area could keep eating and using products from these animals long into the future.

After 1835, European farmers (known as squatters) brought introduced animals such as sheep, cows, goats, and horses to what we now call the State of Victoria. The introduction of these animals (mainly sheep) and the use of European farming practices changed the landscape in terms of the kinds of plants and trees that covered it. As a result, the habitats for native animals were affected. While some native species survived, others became locally extinct (like quolls, bandicoots and bustards [also known as bush turkeys]) because Europeans ate them in unsustainable numbers, or the introduced animals seized their ecological niche. This means that today there is a mix of native and introduced species wherever you go in Australia, from kookaburras to sparrows in the sky, wombats to foxes on land, and blue-ringed octopuses to European green shore crabs in our oceans.

We had kangaroo-soup, roasted [wild] turkey well stuffed, a boiled leg of mutton, a parrot-pie, potatoes, and green peas; next, a plum pudding and strawberry-tart, with plenty of cream. Katherine Kirkland (who lived in Trawalla – 40kms west of Ballarat), Life in the Bush. By a Lady, 1845, p.23.

Here is one of our Education Officers taking visiting students to the Butcher’s Shamble, where miners could buy mutton (this mutton however, is made of plastic).

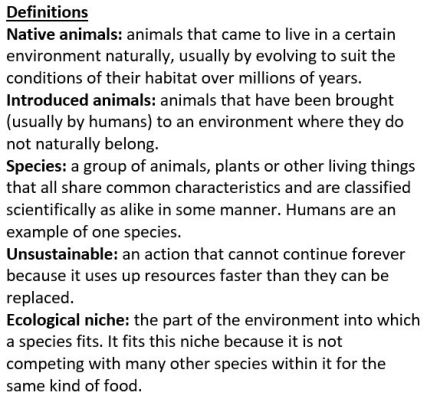

The gold rushes began in 1851 and brought hundreds of thousands of people from all around the world to the shores of Victoria. Many of these new migrants transported yet more animals with them. Dogs were particularly useful companion animals on the diggings because they could keep you warm at night and guard your tent/hut while you were goldmining. For this reason, there are many dogs featured in the sketches of ST Gill, one of the most famous goldrush artists. Some animals were even introduced from the late 1850s onward to help Europeans ease their homesickness! Songbirds like sparrows, starlings and blackbirds were thought to make the Australian bush sound more like England.

The most useful of horse breeds on the diggings were draft horses, also known as Clydesdales – these are the biggest and strongest type of horse.

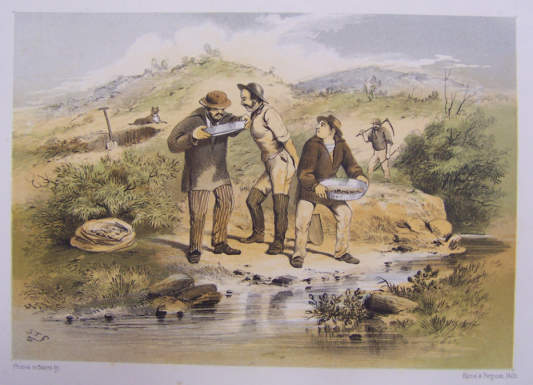

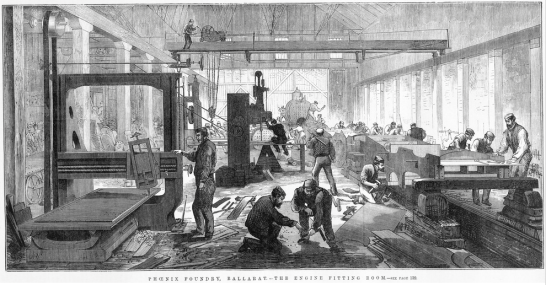

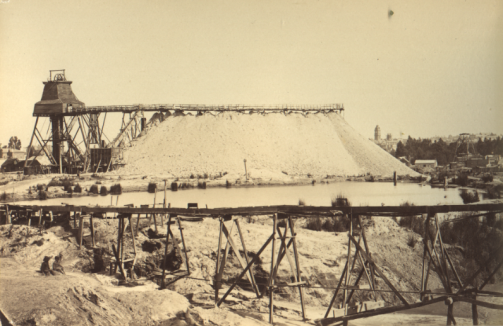

Horses were also in high demand during the early years of the gold rushes (before the need for steam-powered machines increased), as all mining work relied on muscle power. As a horse can typically push/pull the same load as ten people, they were used to lift heavy metal buckets of dirt, rocks and gold from below ground in the first few years of the gold rushes. Likewise, horses could be attached to machines that were used to free gold from paydirt and quartz rock, for example, puddling machines and Chilean mills. People and goods could also move around by horse (or sometimes bullock). They were attached to coaches or other vehicles to transport larger groups of people and/or numerous goods. Cobb & Co built a coach, which was a bit like a modern bus, called the ‘Leviathan’ (a word meaning big monster). This vehicle could carry up to 60 people from Ballarat to Geelong with the help of 16 horses, but it did not prove very successful.

Sheep fat was commonly used to make soap for washing clothes and bodies. Candles could also be made from animal fat.

Many animals were also brought by the new arrivals for food. Goats and cows were milked to produce dairy products to feed miners and their families, while chickens, ducks, geese and turkeys were farmed for eggs and their meat. However, the meat that was most commonly eaten on the Victorian goldfields in the 1850s was mutton (old sheep). You can see many animals around Sovereign Hill which represent the animals that were brought here by goldrush migrants. During a visit, you might even spy our museum cat ‘Fergus’ who helps to keep the mice and rats away from the outdoor museum.

Some animals also toured the Victorian goldfields as entertainment – read about the visits from a tiger, an elephant and two zebras that came to Ballarat in the 1850s here.

Even 19th century ladies’ underwear, like this corset, were often made using animal products – the tough ribbing was typically made of baleen whale teeth, while the smooth lining was made by silk worms (the caterpillar of the silk moth).

Next time you visit Sovereign Hill, perhaps you could take photos to write a story book about the many animals that miners would have encountered on the diggings – from native animals to domesticated pets and animals that produce food.

Links and References

An ABC Education ‘digibook’ featuring Bruce Pascoe talking about traditional Aboriginal land management: http://education.abc.net.au/home#!/digibook/3122184/bruce-pascoe-aboriginal-agriculture-technology-an

An ecological niche explained: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xIVixvcR4Jc

A brief history of Victoria: https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2017/05/18/the-history-of-victoria/

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Europeans in Australia ate native foods to survive: https://cass.anu.edu.au/news/parrot-pie-and-possum-curry-how-colonial-australians-embraced-native-food

SBS Gold on Australia’s introduced species: https://www.sbs.com.au/gold/story.php?storyid=130

A fact sheet on invasive species in Australia: https://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/2bf26cd3-1462-4b9a-a0cc-e72842815b99/files/invasive.pdf

The introduction of rabbits in Australia explained by the National Museum Australia: https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/rabbits-introduced

A blogpost exploring what was commonly eaten by goldrush immigrants: https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2016/11/30/how-to-cook-a-gold-rush-feast/

An online version of Katherine Kirkland’s book Life in the Bush. By a Lady, published in 1845: https://tinyurl.com/yxavj9fh

Information on animals introduced to Australia to make European settlers less homesick: http://myplace.edu.au/decades_timeline/1860/decade_landing_14.html?tabRank=4&subTabRank=3

A blogpost on mid-19th century transport: https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2015/06/25/1850s-transport/

A great Gold Museum blogpost about dogs on the Victorian diggings: http://www.goldmuseum.com.au/canine-companions/

More information about the Leviathan coach: https://blog.qm.qld.gov.au/2017/09/13/how-big-was-the-leviathan-monster-coach/

In the 1850s, animals were even used to create the red colour of raspberry drops. The cochineal beetle from Brazil was dried and ground-up to make red dye. But don’t worry, no living things are harmed in the making of Sovereign Hill’s lollies.

During a visit to Sovereign Hill and the Gold Museum, it’s hard to miss the influence of goldrush artist S. T. Gill.

During a visit to Sovereign Hill and the Gold Museum, it’s hard to miss the influence of goldrush artist S. T. Gill.