Many visitors to Sovereign Hill are surprised to see the vegetable and decorative gardens on display around the Outdoor Museum. Did you know that many of the gardens are inspired by understandings of gardens that existed in goldfields towns like Ballarat? Here, we will explore some of their stories and what they can tell us about life on the Victorian goldfields in the 19th century.

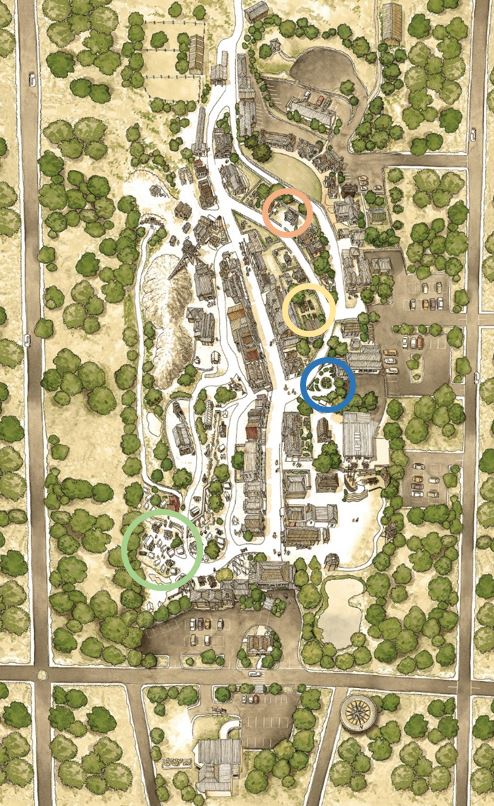

Peppercorn trees like this one were often planted at schools to provide shade and because they were thought to keep bugs away. This tree is identified by the orange circle on the map.

The Sovereign Hill Museums Association gardeners work closely with historians to build the gardens – and even change them from season to season. These spaces tell stories about the kinds of gardens that existed in Ballarat in the 1850s and the people who would have owned them. Some residents of goldrush Ballarat had large, expensive houses and used a beautiful garden to show off their wealth. Other residents grew gardens to feed their families, or provide medicine or vegetables for sale. Trees were also used for shade, to keep the bugs away (such as peppercorn trees), or as posts for displaying advertising posters or important community news. The only lawn you see at Sovereign Hill is next to our modern Café and playspace – back in the gold rush, lawns were not very common because lawnmowers were yet to have motors (they were pushed by hand at this time, which was hard work!) and they were very expensive.

A map of the Sovereign Hill Outdoor Museum showing the location of the gardens and trees featured in this blogpost.

The Bright View Cottage sundial garden and rose arch.

The garden in front of the Bright View Cottage has a typically orderly Victorian design. It shows that the owner can afford to use land for decorative and not just practical purposes. While the garden does include some vegetables and herbs (which were more for viewing pleasure than eating), it also includes formal decorative features such as a sundial and hedged garden beds. A rose arch greets visitors as they enter through the white picket gate into the garden. Perfumed flowers like roses, lavender and daphne were popular because it was believed at the time that good smells kept you healthy while bad smells could make you sick. Many 19th century gardeners were also interested in growing exotic plants and hunting for rare species, which is why gunnera manicata (giant rhubarb) features on the left side of the cottage. This garden is marked on the Sovereign Hill guide map by a blue circle.

The garden behind Linton Cottage full of springtime foods.

There is a kitchen garden located behind Linton Cottage (across the road from the Bright View Cottage) which grows fruit, vegetables, nuts and herbs. Like many people on the goldfields, the owners of such a property improved their position in society by growing food for sale in the grocery store. The trees grown in this garden are apple, pear and walnut. There is also a grapevine along the back fence. The vegetables produced by this garden change with the season, and the herbs are grown partly for their ability to control pests; rhubarb and pyrethrum can be used to keep insects away. This garden also has a compost bin to replace the nutrients in the soil; using the garden scraps to make compost to spread on the garden beds helps plants grow better. There is also a large chicken coop for the production of eggs, meat, feathers and fertiliser. It is marked on the map by a yellow circle.

An example of a productive vegetable garden in the Golden Point Chinese Camp.

These two gardens found in the Golden Point Chinese Camp tell different stories. The first demonstrates the way Chinese miners from the late 1850s onwards produced fresh food for themselves and sometimes the broader community. As most of the Chinese miners had been farmers back home in China, many were skilled at growing vegetables. Typically, these gardens were grown communally. So, they would take it in turns to look after them while others went mining. Some Chinese miners began growing food for sale when Ballarat’s gold became harder to find, changing their work from mining to market gardening.

An example of a medicinal garden owned by a Chinese herbalist.

The second of these gardens in the Chinese Camp would have belonged to a herbalist (whose replica store is close by). Today, we would call him a Traditional Chinese Medical Practitioner. This garden is growing medicines and food that can be used in a medicinal diet to treat certain diseases, although many of the herbs for sale in the herbalist’s would have been imported from China. Both these gardens are identified by the green circle on the map.

Sometimes, the Sovereign Hill gardeners grow slightly different plants than would have been seen on the Ballarat goldfields to keep visitors safe, to respond to pests, and to design gardens better suited to the region’s changing climate. According to the Bureau of Meteorology, Victoria has become warmer and drier since the 1850s. This encourages our gardeners to plant more drought-tolerant species than would have been grown in the past.

The Wadawurrung people – the Traditional Custodians of the Ballarat region – supplied black wattle sap as a diarrhoea medicine to European miners. Many native plants were promoted across the landscape over thousands of years by Aboriginal people to provide food, fibre and medicine.

Some features seen in our gardens are not as they were in the 1850s for quite different reasons. For example, while you can see poppies growing at Sovereign Hill, they are not the opium poppies you might have seen in goldrush gardens in the 19th century; real opium poppies can be turned into powerful drugs of addiction. Finally, foxes only became a pest in Australia after their introduction in Ballarat and Geelong in the 1870s. Therefore, while 1850s chicken coops were not built to keep them out, our chicken enclosures need to be much sturdier, as we do sometimes have foxes in the gardens at night.

Walk around your own garden with fresh eyes. What does it say about your diet, your family’s social status, and our climate today?

Links and References

How to cook a goldrush feast: https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2016/11/30/how-to-cook-a-gold-rush-feast/

The lives of animals on Victoria’s goldfields: https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2019/10/04/animals-on-the-goldfields/

The National Museum Australia on goldrush immigration: https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/gold-rushes

How and why were so many exotic street trees planted in Australia? https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-09-12/curious-central-west-why-peppercorn-trees-were-planted/10231768

Information on pest management plants: https://www.abc.net.au/gardening/factsheets/pest-management-plants/9427576

How compost is made: https://www.abc.net.au/gardening/factsheets/get-composting/9437492

Plant hunting was very fashionable across the British Empire in the 19th century: https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/nature/the-plant-hunters-adventurers-who-transformed-our-gardens-would-put-indiana-jones-to-shame-7936364.html