.A costumed character at Sovereign Hill emptying the contents of a chamber pot. This is yellow cordial, not real urine.

The most valuable and respected role a European woman in the 19th century could undertake was that of housewife. Making a home, which included: raising the next generation (educating children, feeding them a nutritious diet, and caring for them during times of sickness), managing all of the chores, mastering needlework, and being able to make an excellent meal for guests, was an accomplishment that women worked hard to achieve, as many still do today.

This final blogpost in our series on goldrush women focuses on the domestic lives of European women living on Victoria’s goldfields in the 1850s.

The Art of Housewifery

The culture that European immigrants brought to Australia’s goldfields promoted the idea that women should manage the private life of the family, while men should be involved in public life, which included holding a job outside the home. During this time in history, housewifery was a highly honourable family and community role for women, and the majority of women were proud to perform it (as many are today). While 21st century Australian women might not hold housewifery in the same high regard, it is important to respect the status of housewifery back then.

A woman’s success in housewifery depended very much on her education in the ‘domestic arts’ and the money her husband could spend on their household.

One of Sovereign Hill’s volunteers teaching visitors how butter was made by hand in a mid-19th century kitchen.

While some girls were being sent to school at this time in European history, it was much more common for boys to attend lessons with a qualified teacher. Girls instead were typically kept at home where their mothers would teach them how to cook, clean, sew and raise children because these were the most important skills for a woman to have at this time. Girls who were taught to read (which was considered worthwhile by many as they could then teach that skill to their children) could also learn from books on housewifery such as ‘Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management’ (published in 1861). Even if girls had the opportunity to attend school, they were often taught gendered skills like sewing, which was particularly helpful to those whose mothers had died before their skills could be passed on.

Being able to ‘keep a wife’ was an indication of a man’s status, meaning a woman’s clothing, their home and its contents communicated his social and economic success. A European man would have been ashamed if his wife was forced to take a job outside the home to support the family; it was a sign to others that he had failed as man. For a brief time, these European social norms brought to Victoria’s goldfields shifted (read more about this here), but not for long. In the 1850s, almost all of Ballarat’s miners were young men who came to the goldfields by themselves or with their male friends or family. They needed to make some money before they could afford to marry.

Living Conditions for Married Women on the Goldfields

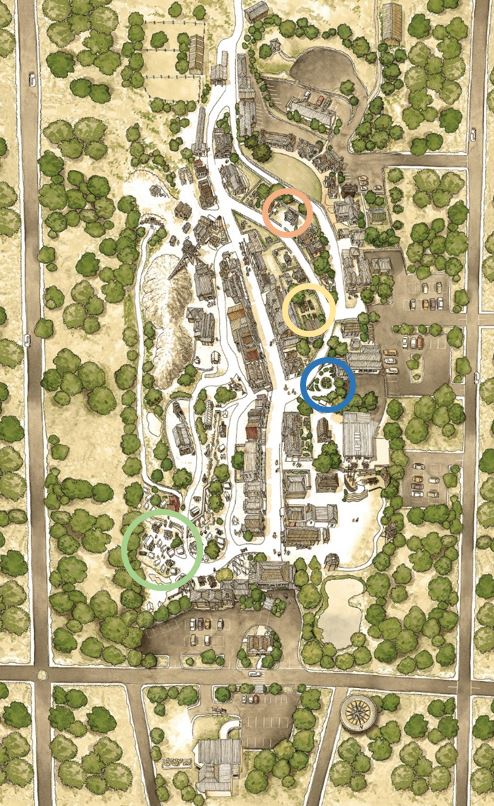

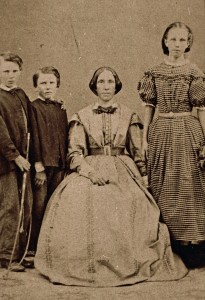

Photographer unknown, Eliza Perrin and her children, c.1860. Reproduced with permission from The Gold Museum, The Sovereign Hill Museums Association. The dress Eliza is wearing here is also in the Gold Museum Collection.

At the start of Victoria’s gold rushes, Europeans on the diggings typically lived in tents and huts. This made it hard for families to keep children healthy and maintain bodily cleanliness, especially during Ballarat’s famously cold winters. However, there were a small number of very resilient women living on the goldfields during this time. It was only in the mid-to-late 1850s, once the community became wealthier and locals started living in more permanent homes (normally made of weatherboards or bricks), that female immigration from Europe increased. This change encouraged the number of families to grow. More hygienic living conditions (including better systems for managing human waste) also made it safer to raise children.

Despite improvements in living conditions, every pregnancy a woman faced was a risk to her life no matter what her social status. Experiencing complications during childbirth was one of the most common causes of death for women until recent history. Until the mid-20th century, most women birthed their babies at home, and if complications occurred, there was a high risk that both mother and child would die. The use of anaesthetics to ease the pain of childbirth was popularised after chloroform was given to Queen Victoria when had her eighth child in 1853. Anaesthetics as we know them today, that enabled caesarean sections to be performed were not available until later in the 19th century. Even then, the risk of death from post-operative infection was still high. A woman could also bleed to death or develop a deadly infection following the successful birth of her baby. Antibiotics and blood transfusions that could save both mother and baby only came along in the 20th century.

Ballarat’s women had a particularly hard time birthing and raising children without the support of their own mothers and older women with childrearing experience. Emily Skinner travelled to Victoria in 1854 and wrote this about her lonely experience of motherhood: “You mothers in England little imagine how blessed you are compared with poor women in the diggings, at this time, especially such as I, who knew nothing about babies and their management”.

Keeping children alive during their most vulnerable early years of life also presented goldrush women with significant challenges. About a quarter of Ballarat’s children died before the age of five in the 1850s, usually from drinking polluted water. Until 1859, people didn’t know that germs existed and were the main cause of disease. At least goldrush women knew not to let their babies crawl on the filthy ground, whether they knew about germs or not. Crawling as a developmental stage in a child’s life only started being encouraged in the late 19th century thanks, in large part, to Germ Theory.

Domestic Technologies

Making a healthy and happy home for a family remains a challenging job for women, even though men today tend to play a larger role in childrearing and undertake more household chores compared to men in the past. Back then, however, housework was much more physically demanding because there were no washing machines, vacuum cleaners or supermarkets. Whether a woman was managing her own domestic duties, or was a maid working for a wealthy family, this job could include many responsibilities such as collecting water (plumbing arrived in Australian houses later in the 19th century), chopping wood, growing and making food from scratch, washing/ironing/sewing the family’s clothes, and disposing of the contents of chamber pots. Lower-class wives frequently washed other people’s laundry or sewed clothes to help pay their family’s bills, while middle class wives owned ‘high-tech’ cleaning technologies (like a charcoal iron instead of a sad iron) to make their chores easier. Wives in the upper classes usually had maids and cooks to do all of this work for them.

Photographer unknown, family outside home, c.1860. Reproduced with permission from The Gold Museum, The Sovereign Hill Museums Association.

One of the most important technologies to affect women’s lives during this time was the sewing machine. On average, it took an experienced sewer about 15 hours to hand-stitch a man’s shirt, but a sewing machine cut that time down to only an hour and a half. Inventions like these became status symbols for middle-class families, and could help many lower-class women make money by producing clothes for sale from the safety and privacy of their homes.

In addition to this busy workload of chores, housewives educated their children, cared for the sick and elderly, and often volunteered for their church. It’s no wonder they used to say “a woman’s work is never done”!

The lives Australian women live today maintain many of the traditions explained in these three blogposts, however, some have been rejected or replaced with new social norms and a focus on gender equality. What do you think Australian womanhood will look like in another 100 or 200 years?

Links and References:

Sovereign Hill Education’s student research notes about women on the Ballarat goldfields: http://education.sovereignhill.com.au/media/uploads/SovHill-women-notes-ss1.pdf

A State Library of Victoria blogpost on women on the goldfields: http://ergo.slv.vic.gov.au/explore-history/golden-victoria/life-fields/women-goldfields

An SBS blogpost about women on the goldfields: https://www.sbs.com.au/gold/story.php?storyid=27#94

Two Sovereign Hill Education blogposts on 1850s women’s fashion: https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2012/02/28/gold-rush-belles-womens-fashion-in-the-1850s/ https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2013/09/06/gold-rush-undies-womens-fashionable-underwear-in-the-1850s/

A Sovereign Hill Education blogpost on general clothing in the 1850s: https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2018/06/19/1850s-fashions-in-australia/

A Sovereign Hill Education blogpost on keeping the floor clean: https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2012/08/28/household-arts-of-the-1850s-sweeping-beating-and-scrubbing/

Two Sovereign Hill Education blogposts on laundry: https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2016/04/22/in-praise-of-washing-machines/ https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2012/02/09/household-arts-of-the-1850s-laundry/

A Sovereign Hill Education blogpost on ironing: https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2012/08/13/household-arts-of-the-1850s-ironing/

A series of videos made by a Sovereign Hill volunteer who attempted to live 1850s-style in one of the small houses within the outdoor museum for a few days: https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2013/03/05/household-arts-of-the-1850s-a-personal-experience/ https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2013/03/20/household-arts-of-the-1850s-part-2-the-first-night/ https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2013/04/03/household-arts-of-the-1850s-a-personal-experience-part-3/

A Sovereign Hill Education blogpost about Lola Montez: https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2017/07/19/who-was-lola-montez/

A Culture Victoria webpage about the few Chinese women living in 19th century Victoria: https://cv.vic.gov.au/stories/immigrants-and-emigrants/many-roads-chinese-on-the-goldfields/voyaging-to-australia/who-were-they/nearly-all-men/