Hallowe’en is often considered a recent addition to Australian celebrations, imported from the United States. However, Halloween’s roots go back thousands of years to Celtic traditions in Ireland and Scotland, and here in Australia to the nineteenth century.

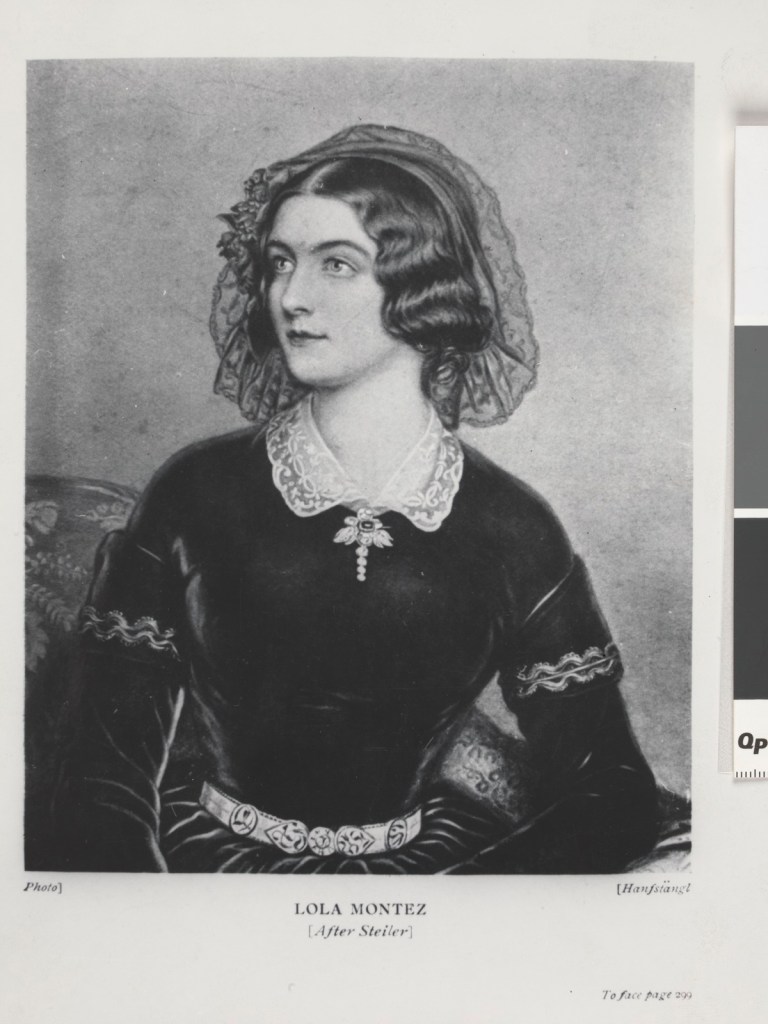

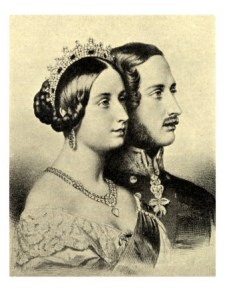

All Hallow’s Eve adopted the Celtic festival of Samhain, which celebrated the end of summer and a thinning of the line between life and death. As the season turned and the days started to get shorter and darker, it was incorporated into the Christian calendar with All Saints (All Hallows) Day. By the early nineteenth century, many of the traditions we associate with Halloween were firmly entrenched. Carved vegetables, like turnips, were used as rough lanterns for celebrations in the dark and sometimes carved with faces to scare off evil spirits. People would dress up to confuse wandering spirits; children in costume would wander from house to house in costume receiving offerings of fruit or nuts and sometimes singing or reciting poetry in return. This was known as guising, today it is known as trick-or-treating. Bonfires and fortune-telling were common practice, and Queen Victoria herself was known to love the Halloween festivities at her Balmoral property in Scotland.

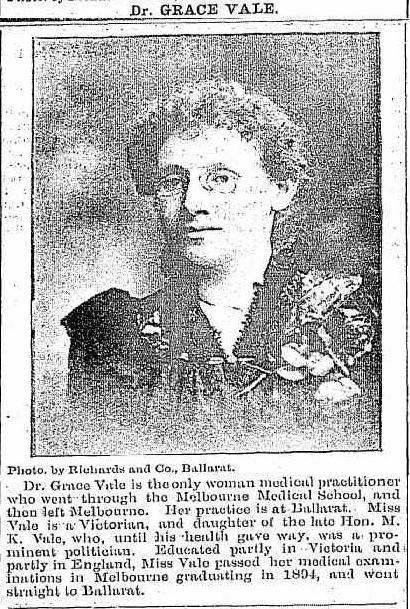

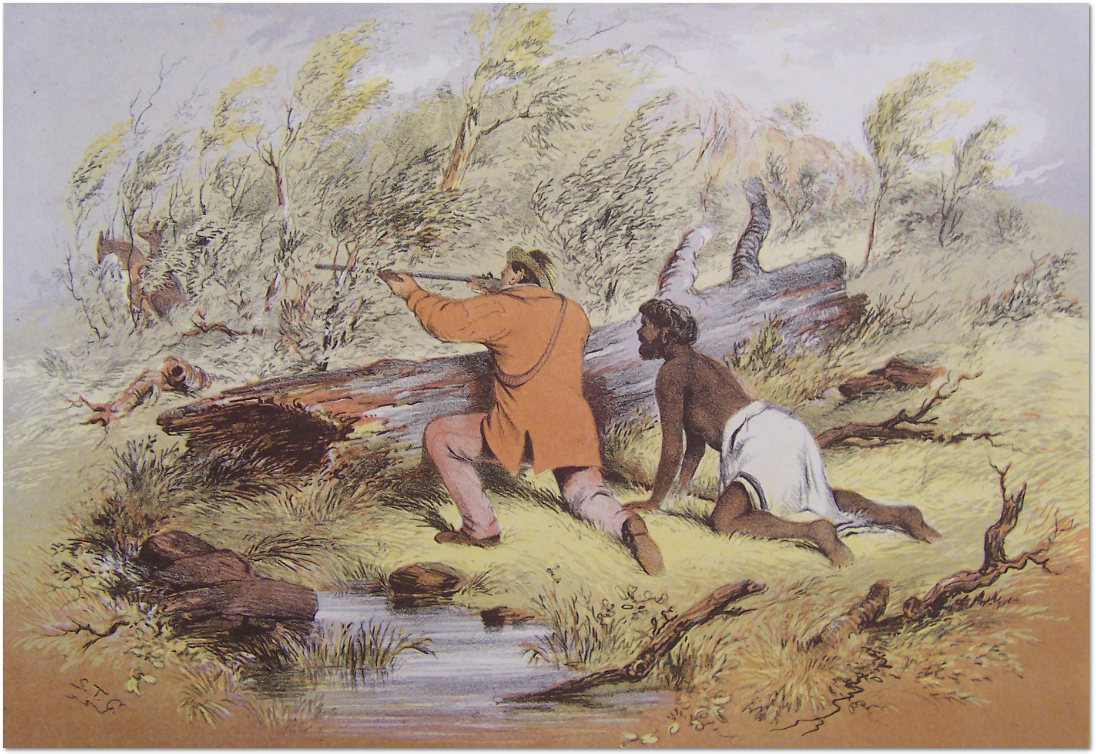

In the mid-nineteenth century, we saw the mass migration of large numbers of Irish and Scottish people around the world, estimated at 90,000 people, including to Australia. Driven by the potato famine, disease wiped out potato crops in Ireland and Scotland leading to widespread starvation in rural communities, and land clearances, the forcible eviction of cottage farmers to enable large commercial farms, along with the lure of gold large numbers headed to the colony of Victoria. In the 1854 Victorian Census, the largest migrant group, after English and Irish, was the Scottish.

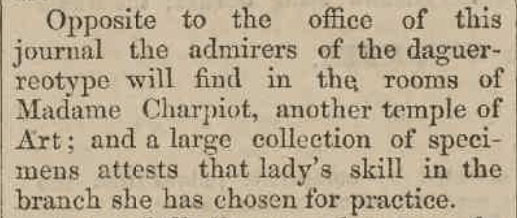

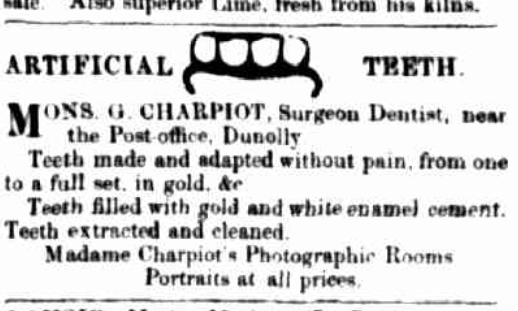

In moving to a new country our Scottish migrants brought with them many traditions from home, food, music, and festivals. These traditions became really important in maintaining a connection to family and culture from the other side of the world. Scottish, or Caledonian Societies sprang up across Victoria as a way of connecting with people. They were an important part of community-building. From our Caledonian Societies, we get one of our earliest references to Halloween being celebrated in Australia.

What to expect at a Halloween Ball…

Music and dancing!

If you attended a Halloween ball in 19th-century Victoria, you would likely enjoy music, dancing, and traditional Scottish country dances. One popular dance was the Flying Scotsman, inspired by the famous steam train.

Watch the video to learn the steps to the Flying Scotsman, or view the written instructions HERE

Poetry reading.

The work of Scottish poet Robert Burns was very popular. His poem, Halloween, which covers many of the folk fortune-telling, match-making games was adapted into a ballet that toured the gold field towns to great enjoyment. His poems include a mix of Scots and English dialect. Can you read a stanza?

Among the bonny winding banks,

Where Doon rins, wimplin' clear,

Where Bruce ance ruled the martial ranks,

And shook his Carrick spear,

Some merry, friendly, country-folks,

Together did convene,

To burn their nits, and pou their stocks,

And haud their Halloween

Fu' blithe that night.

Try writing a poem inspired by Robert Burns?

Trick or Treat.

Practice guising (trick or treating) by taking turns presenting poems to classmates.

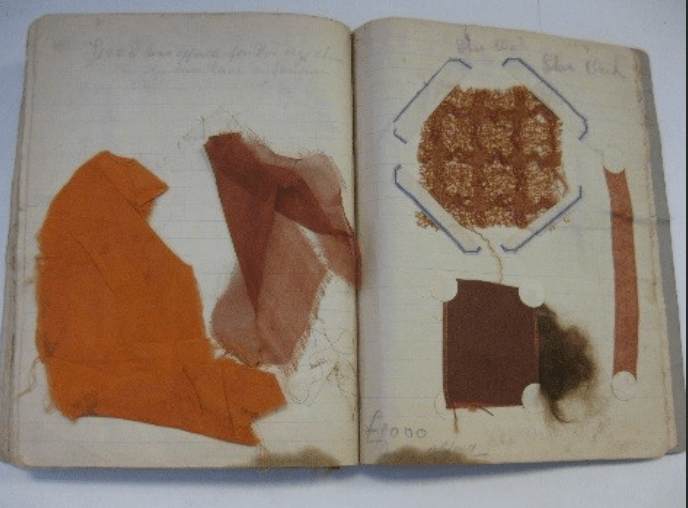

Here is some inspiration for your poem from our own Scottish community on the diggings of Ballarat sourced from the Centre for Gold Rush Collections. Break the classroom into 4 groups and allocate an item to each group to work on a poem either as a group or individually. Use the following prompts to help identify the artefacts.

- Create a list of describing words (colour, shape, size)

- Create a list of sensory words (sound, taste, smell, feel)

- What makes your thing unique? (scratches, repairs, stains)

- Word association (what else does it make you think of?)

- What is it?

Sampler [83.4665]

Piece of embroidered linen with the alphabet, and flowers in cross-stitch. Name embroidered: Jane Patterson. Jane Patterson migrated to Ballarat from Scotland in the late 1850s. She married Phillip Waterson in 1860. A 12-year-old Jane made the needlework sample in 1854 when she was in school in Scotland.

Hair chain [84.0503]

A long chain of three intertwined strands composed of human hair held at intervals by Gold clips. Link join has a small wooden pipe attached which contains 4 views of Scotland. Hair comes from Donor’s Aunts in Scotland.

Rolling pin for Scottish Oatcakes [79.0593]

Wooden rolling pin ridged for making Scottish Oatcakes. This belonged to Mathilda Lang who came to Australia in 1855 in the Sailing Ship The Star Of The East to join her husband in Ballarat, bringing with her their five children. Her husband Thomas Lang built a house at Warrenheip and had extensive nursery gardens there till they moved to Melbourne in about 1869. He came to Australia in The SS Great Britain in 1854 from Kilmarnock, Scotland. [Thomas’ story ]

Leather Purse [83.4669]

Small leather purse with a short leather strap. There is a brass clasp and the front is decorated with stars of mother of pearl and a brass stud in the centre. Purple paper lining, with a leather light tan colour body for a purse. It is Worn by Jane Patterson who migrated to Ballarat from Scotland in the late 1850s. She married Phillip Waterson in 1860. An 18-year-old Jane drove in a bullock dray from Ballarat to Buckley & Nunn’s in Melbourne where the dress was made. Purse worn on the belt of the wedding dress (83.4664) expandable with concertina sides.

If you were to travel to a new home far away, what traditions would you take with you?