Supermarkets, refrigeration, and the food pyramid were invented a long time after the Victorian gold rushes of the 1850s. During this time in history, most food on the goldfields was either grown fresh in your garden, imported in a dried state (like rice, flour and lentils), or pickled/preserved (like jams, stewed fruit and tinned anchovies). Some bush foods were hunted down by miners or supplied to them by Aboriginal people, but most new arrivals to the diggings had to work hard for their dinner. The rich could afford healthier diets than the poor, but life expectancy (the average length of time that people live in a particular country) was quite low in comparison to Australia today. Poor nutrition, dangerous work and deadly diseases worked together to make life on the diggings relatively short and harsh.

Australians now live much longer lives than they did during the 19th century thanks to improved diets and medicine. This graph shows how life expectancy has increased for both men and women between 1884 and 2009. Reproduced with permission of the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

S. T. Gill’s sketch of a ‘Butcher’s Shamble’ from 1869 demonstrates life before refrigeration and modern hygiene.

Most miners in 1850s Ballarat happily ate damper (campfire bread) and mutton (old sheep – ‘lamb’ means young sheep), as such a meat-heavy diet was only affordable to the rich back in Europe at this time. However, this diet isn’t very nutritious. It lacks important vitamins and minerals that the body needs, which can be found in fruit, vegetables and nuts. While such a limited diet will keep you alive, it can make your body – brains, bones, organs – age must faster than people who eat a broader range of foods. A diet of damper and mutton could make you more likely to get sick, and you would stay sicker for longer. However, the goldfields butcher wasn’t too worried about the nutrition of his customers – butchers were often the richest people on the diggings!

The reason sheep were so common on the diggings was because of Victoria’s earlier history of colonisation. The first European settlers/invaders, who arrived from 1835 onwards, were here on the grassy plains of Victoria to farm sheep. By 1851, the year the Australian gold rushes began, there were over 6 million sheep being farmed across the state (according to the National Wool Museum). The sheep farmers (often called ‘squatters’) realised that instead of boiling down their old sheep for tallow (fat for making soap/candles), they could sell them as food to the thousands of hungry miners. News of cheap meat on the Victorian goldfields attracted thousands of people to the diggings (Blainey, G. Black Kettle and Full Moon, Penguin Books Australia, 2003, p.197). Luckily, by the 1860s, the gold rushes had also attracted many Chinese miners, who used their farming experience to grow productive market gardens full of nutritious vegetables which would have improved the general health of many Victorians at this time.

S. T. Gill’s ‘John Alloo’s Chinese Restaurant’ sketch from 1855 demonstrates the many contributions the Chinese made to diggers’ diets during the Ballarat gold rush. Reproduced with permission of the Gold Museum, Ballarat.

If a man had brought his mother/wife/daughter with him to the diggings, he was bound to have a better diet than a single man. Many goldrush women in the 1850s came to Ballarat very well prepared, as they brought bags of seeds and small animals with them to ensure the family didn’t starve (Isaacs, J. Pioneer Women of the Bush and Outback, Lansdowne Publishing Pty Ltd, Sydney, 1990, p.100).

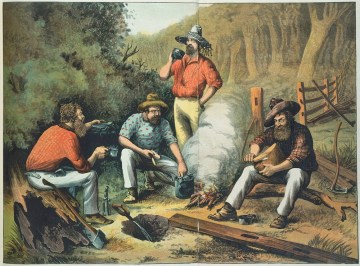

Cooks didn’t use many utensils when creating meals over a camp fire, but a simple mixing bowl, knife and camp oven (also known as a Dutch oven) were all one needed for baking bread, roasting a leg of lamb, or making stews/soups. Next time you go camping, you could try cooking like a goldrush miner!

Here are some of our favourite 1850s goldrush recipes which you could try at home or school:

Links and References

Sovereign Hill’s other blogposts about goldrush food: https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2013/03/19/what-was-eaten-on-the-goldfields/

https://sovereignhilledblog.com/2013/04/15/what-was-eaten-on-the-goldfields-part-2/#more-1069

SBS Gold on goldrush food: http://www.sbs.com.au/gold/story.php?storyid=66

Goldrush food: http://www.egold.net.au/biogs/EG00116b.htm

A great video about 19th century British diets: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t5dr8WSPhzw

Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1861), maybe the most famous cookbook of all time: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mrs_Beeton%27s_Book_of_Household_Management

The British Library on food of the 1800s: http://www.bl.uk/learning/langlit/texts/cook/1800s2/18002.html

19th century menus: https://19thct.com/2012/08/11/a-menu-from-the-early-19th-century/

The most dangerous jobs in the 19th century: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=glfVNlwv8bQ

Life for women on the early Ballarat goldfield: http://education.sovereignhill.com.au/media/uploads/SovHill-women-notes-ss1.pdf

Another webpage about the lives of goldrush women: http://www.egold.net.au/biogs/EG00115b.htm

Changing mealtimes and their names in history: http://backinmytime.blogspot.com.au/2012/08/a-bit-about-meals.html

Fantastic BBC food in history documentary: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I7FRQjdSHWk

Blainey, G. Black Kettle and Full Moon, Penguin Books Australia, 2003.

Isaacs, J. Pioneer Women of the Bush and Outback, Lansdowne Publishing Pty Ltd, Sydney, 1990.