At Sovereign Hill we are often asked about the experiences of women in the past; in particular, limitations on their dress, behaviour, education, and job opportunities as compared to men. Values, beliefs, and even some science of the time promoted the idea that men and women were inherently different and that this then justified their different treatment and access to opportunities. STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) fields in the nineteenth century provide us with stories of amazing women, who were engaging, inventive, inquisitive, and pioneering in their respective fields.

MADAME ELIZABETH CHARPIOT: Daguerreotype

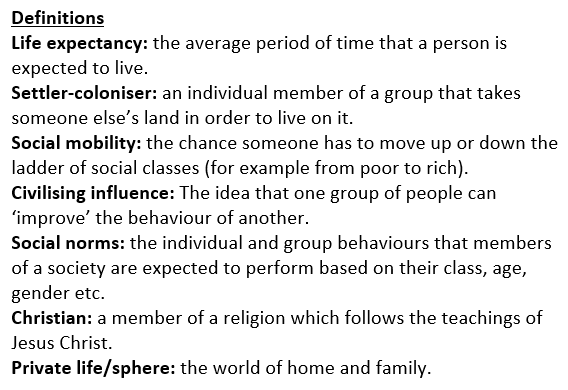

Elizabeth Henwood, with her younger brother and sister, arrived in Port Phillip Bay aboard the Barque Velore in 1853. They made their way to the Victorian goldfields where in 1855 Elizabeth married George Charpiot, a watchmaker and dentist. It is unclear where her training or equipment came from but by 1856 Elizabeth had set herself up as a photographer, perhaps one of the earliest female photographers in Australia. Within her husband’s jewellery and dentistry business, she had a set of photographic rooms. The Ballarat Star, whose offices were opposite the business commented on her skill:

A daguerreotype is the first form of commercial photography. A silver-plated copper plate was treated with a light-sensitive material that reacted when exposed to light. The plate was developed and fixed in a chemical bath, so it was a unique, single image. Our collection includes several examples of daguerreotypes like the style that Elizabeth was producing. The daguerreotype below is carefully mounted and beautifully framed. The lady is wearing several pieces of jewellery and carefully holding a book open – why do you think she chose to include a book in her picture?

If you had your picture taken, would you wear anything special?

What one special object would you want to be included?

When the Charpiot’s moved to Dunolly, both continued their businesses; Madame Charpiot’s portrait services were regularly advertised alongside her husband’s dental business.

A few years later they moved again to the goldfields town of Tarnagulla. On New Year’s Day 1868, their business caught fire and was destroyed. Most of Elizabeth’s photographic equipment was likely lost and it would seem she never returned to professional photography after the fire.

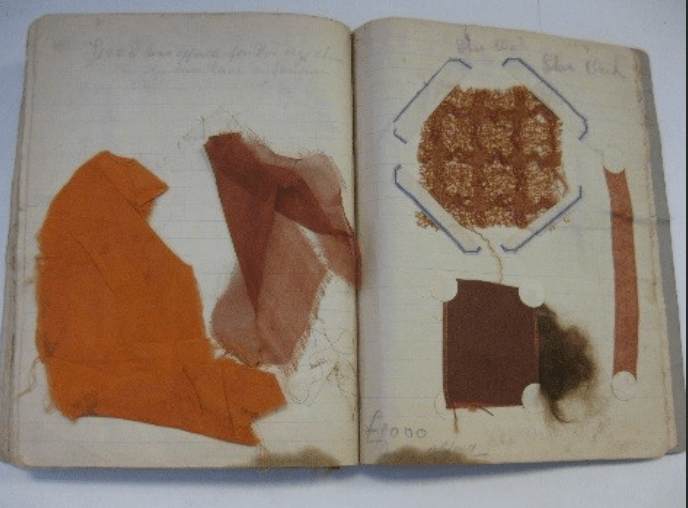

EADY HART: Inventor

Eady Hart arrived on the goldfields in 1854 as a six-year-old, with her family seeking gold. She became a dressmaker and married engineer William Hart. It seems to have been a difficult marriage and William deserted Eady and their eight children. Eady was remarkably resilient, she supported the family, including six foster children, with her sewing and millinery skills, then taxidermy, then an innovative fire-lighting product. Eady was curious and innovative and turned her attention to dyes. In her small kitchen, she experimented with native plants, like grass trees, to produce a beautiful range of natural dyes – useful for fabric and foodstuffs. Here she met with great technical success. Thirty years of experimenting led to the formation of Hart’s Royal Dyes in 1921. In our collection, we care for a number of her recipe and sample books, along with patent applications and business correspondence.

What is a patent? Why would Eady need a patent for her idea?

Eady had to solve various problems with her experiments. She needed to figure out what colours different plants produced, what was required to make the colour stable and stick to fabric, and whether the ingredients were safe to work with when mixed together. She also had to ensure there were enough ingredients to make lots of dye, and that the recipes were repeatable for others to follow.

People loved the colours Eady created; she won awards for her colours and her dye-making process. Newspapers were filled with reports of her wonderful discovery and for seeing the Australian bush as a sustainable resource: “Mrs. Hart says she has barely tapped on the possibilities of our vegetation. The glory of the Australian bush is not yet known … Mrs. Hart regards as criminal the ruthless cutting for firewood and building purposes valuable timber that should be producing priceless dyes”1

EUPHEMIA BAKER: Artist & Photographer

For Euphemia Baker, the move to Ballarat as a young girl to live with her grandparents opened to her the world of the Ballarat Observatory and the technology of the camera. In our collection we have a photo of young Euphemia “Effie” Baker with her grandfather, Captain Henry Baker, who ran the Ballarat Observatory, standing beside a large telescope. A retired sea caption, Baker was a master instrument maker, and his daughters grew up around the telescope and observatory. Access to this world inspired in them a love of looking at life through a lens for art and science.

His daughter Elizabeth Baker became a photographer and astronomical assistant at the observatory, down the road from where Sovereign Hill is situated in Golden Point. In 1896, the Ballarat Star noted that Miss Baker had taken charge of the observatory, the meteorological equipment and was contributing to international research projects and winning awards for her astronomical photography2. When her young niece, Effie, came to live with the family she gifted her a camera and mentored her in photography. Both Elizabeth and Euphemia were noted for their photography, including photos of the moon and stars taken through the telescope.

Where do you find inspiration?

The Goldrush Centre holds several early cameras, including this quarter-plate camera, perhaps similar to the one gifted to Effie, and the camera belonging to astronomer Mr John Brittain, who lectured in astronomy at the Ballarat School of Mines.

DR. GRACE VALE: Doctor

Were women treated equally in science and medicine?

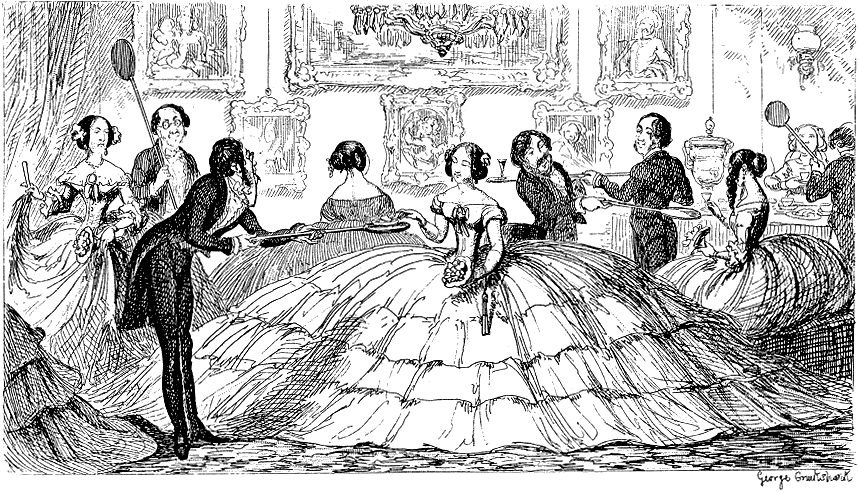

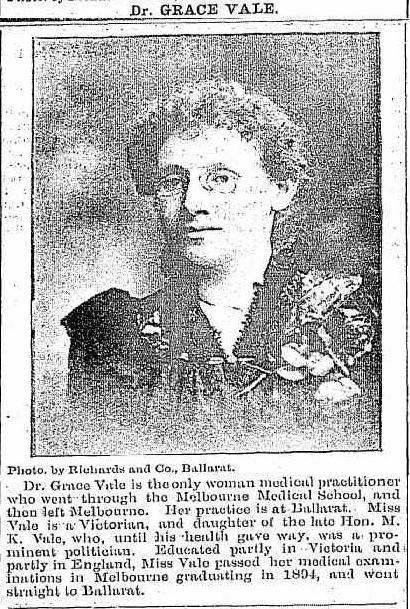

As a founding member of the Victorian Medical Women Society, one of the first female graduates from medical school in Melbourne, and then the first woman public vaccinator (in 1910), Dr. Vale became both a doctor and an active public figure in Ballarat, including being highly active in the suffrage movement to give women the vote. She was present for the first X-rays experiments at the Ballarat School of Mines.

The article below gives a hint of the medical environment in which Dr Vale worked. The “medical profession for women” suggests that only part of the profession is open to them and they are always described as “woman” or “lady” doctors specifically. She has been working in the practice of another woman doctor, Margaret Whyte with whom she had graduated. Her appearance, rather than her abilities, becoming the focus of newspaper articles. In closing remarks, she is described as “the tallest of all the lady doctors, and commanding in appearance.”

Dr Vale used her position to lobby throughout her career for the rights of women. She was active in advocating for free or low-cost healthcare for female factory workers in Melbourne, she was elected to the Ballarat City Board of Advice and spent much of her career as a Medical Officer for schools in Victoria and NSW.

These four stories are amongst many examples of resilient, adaptable, and curious women on the goldfields. But this is just the beginning… what stories can you find? Do challenges still exist today for some groups wanting to enter STEM fields and how can we learn from these pioneers in the past?