The decision to migrate is not one to be taken lightly. Where will you go? How will you get there? What will you take with you? And, what (and who) will you leave behind?

The 19th Century is a world of mass migration – boats carrying vast numbers of people and goods to the far corners of the globe. Migrants face a challenging trip over, cramped conditions, heat and cold, unpleasant food, homesickness, and anxiety over the unknown.

Pictured: Travelling trunk, Sovereign Hill Museums Association collection.

To pass the time aboard ship many passengers kept diaries. Where possible they sometimes wrote letters home – sending them via returning ships they passed on the voyage over. These letters and diaries were treasured. Many obituaries to our migrants reference the journey over; this is a defining decision in their life and a story they may have told many times. Several travel letters and diaries have found their way into our museum collections and they give us a passenger-eye view of life aboard ship.

One diary in our collection, twelve pages from the journey of Thomas Ballingal, describes his journey to Australia and back to Scotland from the diggings. At one point he mentions sending a letter from Melbourne to his mother back in Scotland, knowing it will take 90 days to reach her!

On his return to Scotland he does some sightseeing in London and Liverpool. On Friday 28th November, 1856, he notes:

While in Liverpool went with Mary Martin & Robina to see the Picture Gallery – did not think much of the Picture that took the prize but saw some others thought much better as the “Thurscape Goat” – “Last of England” and “Arrest of John Brown in the time of Henry VIII”.

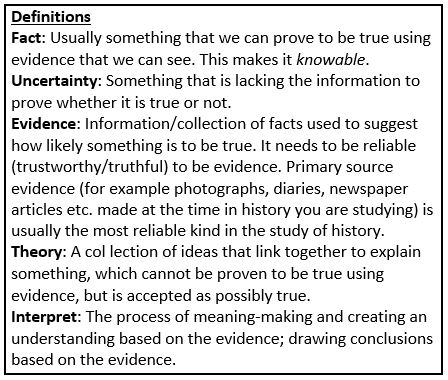

Pictured: Ford Madox Brown, The Last of England, 1852-55. Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery.

This painting remains an iconic image of the migrants’ journey, particularly for the more than 60% of our migrants that made the journey from Great Britain. Although he never made the journey himself, Brown captured the feelings and atmosphere of leaving the familiar behind and the unknown journey ahead.

Pictured: Shipping manifest listing David Wilson aboard the Donald MacKay 1855. VPRS 947/P0000, Jul – Sep 1855.

Another diarist in our collection, baker David Wilson, of whose diaries we again hold only a part, describe conditions aboard ship in shared accommodation. He is travelling with his new wife Grace who struggles with seasickness aboard ship.

Conditions aboard the Donald MacKay are made all the more crowded as the Captain takes aboard hundreds of Irish passengers bound for Van Deimen’s land whose ship has foundered. The ship carries over 600 passengers.

The shipping manifest on arrival indicates that provisions, food aboard ship, was not good: “Numerous complaints among passengers of bad provisions”. Some passengers packed a selection of their own foods to improve their diet. On the goldfields Wilson sets himself up as a baker in Golden Point and appears to have been in business for a few years.

Got up into our little bed – had both of our heads 2 or 3 times knocked on a large beam directly above our head – got up in the morning – unpacked our boxes roped them up again had a desperate struggle for our breakfast and soon found out that a great number of Irish Emigrants – who had been ship-wrecked in the “Ship – Fortune” were to be crammed in amongst us – truly they were amongst the lowest of the Irish – I had ever been in lodgings with – another desperate fight for Dinner – “might being right”

…

Ship lying so much leeward – our tea service rolled down to the other side of the table – Grace filled and as fast as she did so – so did the teacups run away towards the foot of the table – the water coming in to our beds in great drops wetting all our bedding – so much so that we both slept on the forms – I slept sound – but whilst I did so the ship was lying entirely on her side the sea running over her bows – most of those who were awake were praying – or _? _? could neither get into Bed nor a seat – Grace I believe was amongst this number – not being fallen asleep – so soon as I was – the sailors were kept at the pumps for hours – and an extra one put up on the low side of the ship – tins & crockery was (?) crashing – and strolling up and down everywhere – some were actually thrown out of their beds.

Pictured: A note has been added at the end of the Donald McKay passenger lists particularly noting passenger complaints about provisions. Passenger List Donald MacKay, 1855.

To plan your journey you relied on conversations with returned migrants like Thomas Ballingal or their families, letters from abroad and newspaper clippings. Emigrant guides were also available to help you plan your journey.

Our museum collections hold several examples of these guides, including: Gleanings from the Goldfields: A Guide for the Emigrant in Australia: by an Australian Journalist published in 1852 and Gwlad Yr Aur; Neu Gydymaith Yr Ymfudwr Cymreig Australia also published in 1852, a Welsh-language emigrant’s guide to the goldfields. ‘Gwlad Yr Aur’ means ‘Land of Gold’, alluding to the idea that gold has become a primary motivator in the decision to emigrate to Australia.

In their advice to emigrants the author reminds migrants that the ship provides very little – you must bring your own mattress, pillows and blankets, dishes, cutlery, containers for water, some extra food (!) and soap for washing, and sufficient clothes as you will do very little laundry aboard ship!

The guides’ highlight the abundance Australia has to offer:

Of the multitudes attracted thither by the gold discoveries, a large proportion must necessarily be unfitted by their physical constitution and their previous habits for… [this] kind of work…. These persons need not, therefore, by any means despair… Many lucrative employments will fall to their lot… less precarious than those of the gold-digger.

For our migrants, while gold is a big pull factor challenges in their home country, poverty, civil unrest, famine, for example, are pushing them to seek new opportunities. These guides are selling Australia as a land of plenty, beyond gold, for everyone.

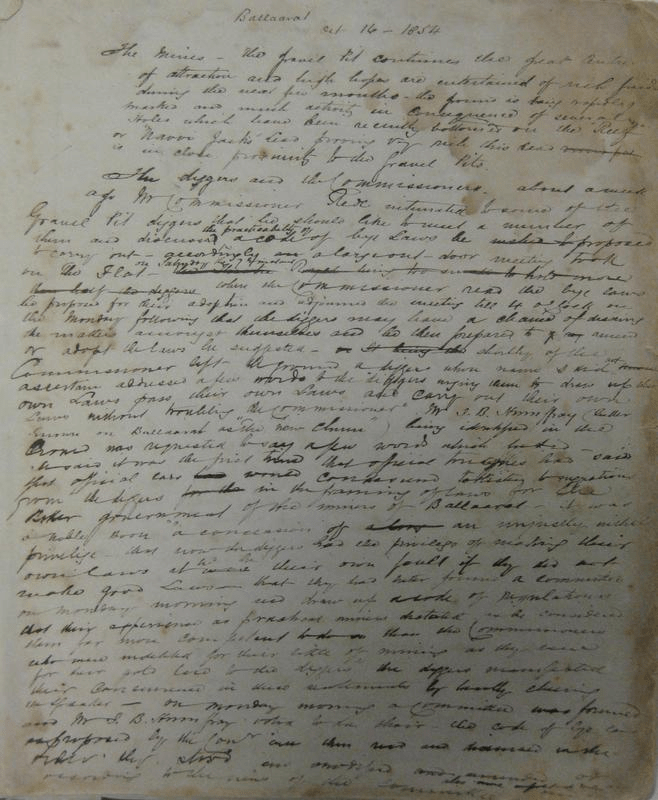

Pictured: page from J.B. Humffray’s Journal 1853-54. Sovereign Hill Museums collection.

Welsh migrant J. B. Humffray found himself aboard the ‘Star of the East’ in July 1853 alongside his brother Frederick. While aboard he kept a detailed diary, the following are excerpts:

8th July 1853

The Surgeon – Mr King – called all the passengers together and read the Rules of the Ship – and urged upon the passengers the importance of cleanliness care of fire &c &c –

This our 3rd day and the rations are being delivered out in a much better manner today than before a Classification of passengers takes place tomorrow between the 1st & 2nd class passengers – I will dine one hour earlier – most of the passengers are in good health and spirits

16th July 1853

[upset that there is very little distinction between 2nd and 3rd class passengers. 2nd class passengers are protesting]

That he would insist upon the Between decks being cleaned out daily before breakfast – I explained to him that it was the wish of every 2nd class passengers that the deck should be so cleaned the matter of dispute was as to whose duty it was to clean it – C – It is clearly laid down in the act that the passengers must clean their Berths every morning & carry the dirt out – I told him we were willing to clean out our Berths but we did not like to clean up the floor of the Between deck inasmuch we were lead to believe that parties would be appointed to do that.

5 Sept 1853

– the vessel rolling very much I was trying in vain to write some fresh copies of the Rules to put up in different parts of the ship – I had to hold myself up with one hand as I tried to write with the other.

* * *

Excerpts from diaries such as Humffray’s were often transcribed and sent back overseas to families and published in pamphlets and newspapers to be shared with prospective migrants. Other peoples’ journeys were an important source of information when making your own plans. Much of Humffray’s diary is in shorthand, and likely intended as a private record; however, six weeks into his journey he noted down some ‘Advice for Intending Emigrants’ in his diary, very similar to the guides, including the following:

- See the ship’s Berths and general accommodation – Cooking Galleys – Water Closets – pumps – tables – seats &c

- Be careful in forming your messes – for much of your comfort depends upon this – do not be in a hurry to form a mess at the bidding of the Cooks and Purser for their accommodation [a mess is a group of people you will eat your meals with]

- Bring with you some hams & Bacon as you will find it very useful in crossing the Tropics & indeed I may say during the voyage – Bring some Baking powder – pickles and some preserves of preserves. …

- the Berths are very narrow & it is unpleasant to have too many things in them – a few good books essential you can steal an hour occasionally for an intellectual repast out of the noise …

- Bring as few clothing as you can do with. It is of little use putting on costly clothing on Board ship unless you are disposed to be arrogant – as they soon get spoiled …

- 3 Blue flannel shirts & 2 Gurnsey shirts are very comfortable and useful

- 3 pair of Ducks 2 pr of Cords –

- 2 pr of Deck slippers – a pair of water tights – as the Decks are frequently flooded – and wet feet are unpleasant indeed while I write the vessel is lurching violently & shipping heavy seas get a Nor-Wester cap –

- Water proof coat & leggings

- A good stock of common coloured sheets

- add to the above – a good stock of courage – firmness – patience – forbearance – cleanly habits forbearance and confidence in the great I am – who holds the waters in the hollow of his hand & you may thus hope for as much comfort as is to be found on Board an Immigrant ship…

* * *

You must be prepared for a great deal aboard ship, Humffray describes both stifling heat and slushy snow aboard ship over the course of their journey.

His journey to Melbourne took 75 days and carried 500 passengers, only half of whom are listed on the passenger manifest. Steerage passengers, the lowest class of traveller, are often not listed beyond a total passenger count – they are just a number. Humffray, as a second class passenger, is named.

VPRS 947/P0000, Aug – Dec 1853.

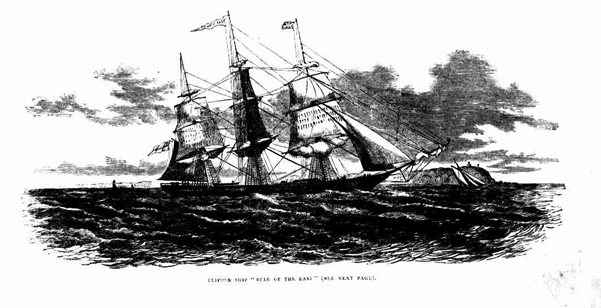

The ship continued on from Melbourne to Sydney and from there to Shanghai. In Sydney an image and description appeared in the Illustrated Sydney News praising the clipper as one of the finest to arrive in port; newly built earlier in 1853.

Pictured: ‘THE CLIPPER SHIP “STAR OF THE EAST”‘, Illustrated Sydney News (NSW : 1853 – 1872), 22 October, p. 2.

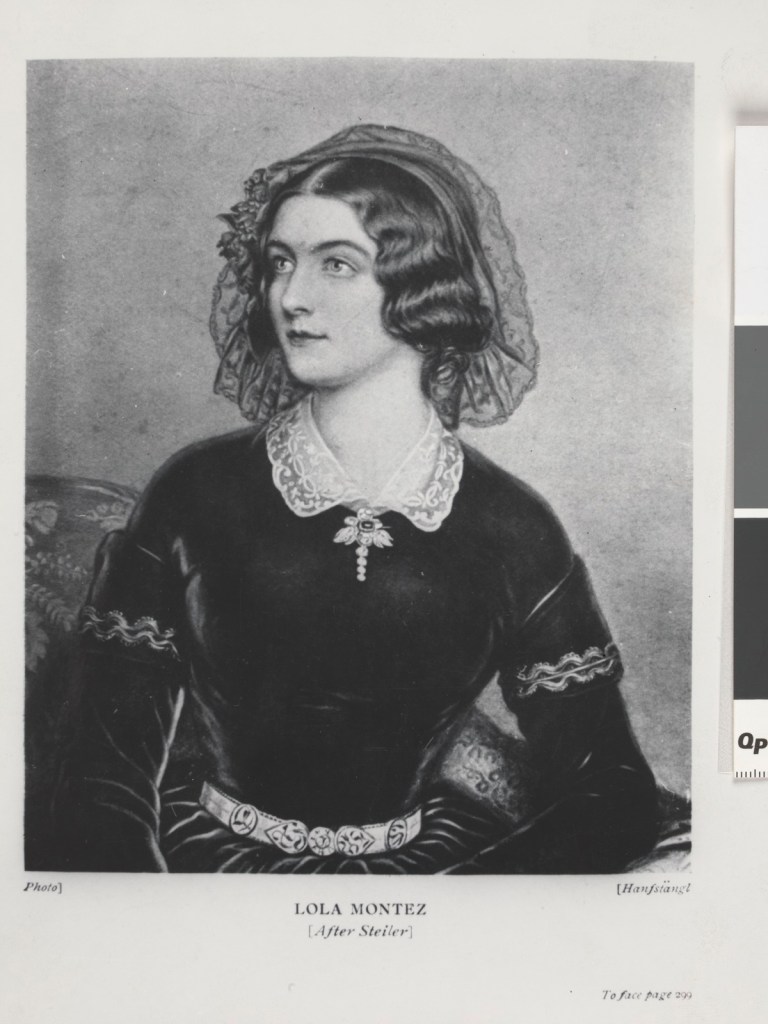

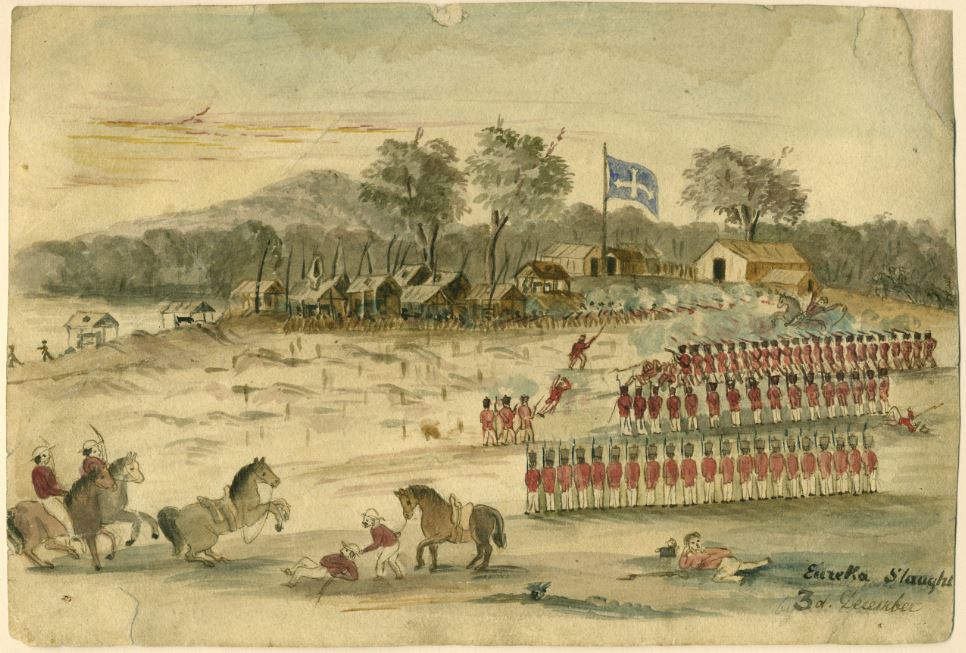

Humffray would go on to be a key figure in the political unrest of the Ballarat diggings around the Eureka uprising. Even aboard ship you can see his interest in fair roles and rules, as he leads passenger petitions to the Captain and commits to recording and circulating shipboard rules. He was secretary of the Ballarat Reform League, and later elected alongside Peter Lalor as a representative in the Victorian Legislative Council (later Legislative Assembly). His brother went into business as a printer and stationer, unsuccessful in Ballarat he moved his family with greater success to Dunedin, NZ.

The journey to the diggings is just the beginning, but the experience aboard ship, the partnerships formed on the months over could have a big impact on the new life that lay ahead of you. Would you make the journey?

Explore more of our diaries and letters here.

Written by Sovereign Hill Education Officer Sara Pearce

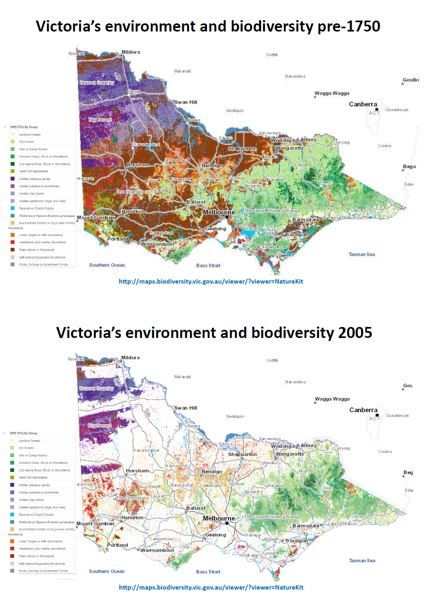

After 1835, when hundreds and then thousands of European

After 1835, when hundreds and then thousands of European